|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

Norman

Jacobs

Page |

| |

Archie Windmill

Nobby Stock

Malcolm Simmons

Ginger Lees

Phil Tiger Hart Hackney 1938

Stan Stevens

Origins of Speedway

Mike Broadbank

Rye House 1961 |

| |

| I suppose it could be said that my

interest in speedway began the day I was born as I was named after

a speedway rider, Norman Parker, then captain of

Wimbledon (writes Norman Jacobs). |

| |

| My family had been keen speedway

supporters since before the War, in particular my uncles Albert

and Joe, my father's brothers. Sadly, Uncle Albert died a few

years ago, but, at the tender age of 94, my Uncle Joe is still a

regular at Lakeside and Kent Kings. Together with a friend of

theirs, Joly Parker, they visited most of the London tracks, some

weeks managing to fit in a visit every night - Wimbledon on

Monday; West Ham, Tuesday, New Cross, Wednesday: Wembley,

Thursday; Hackney, Friday and Harringay on Saturday. Those were

the days in the capital! |

| |

| As far as I know my own father didn't go

to speedway before the War, but in the late 1940s he, along with

my elder brother, John, were regular visitors to Harringay

Although they went to Harringay every week, for some reason my

brother supported Belle Vue and it was because of this that I got

my name, Norman. John's favourite rider was the Belle Vue captain,

Jack Parker. Norman was, of course, his brother, so John felt that

if it was good enough for his hero to have a brother called Norman

he should have one too. So, when I was born, he persuaded my Mum

and Dad to do just that. |

| |

| My earliest memory of speedway is seeing

the World Championship Final on television some time in what must

have been the early 50s at my grandparents' house and how everyone

laughed at the way the commentator pronounced Ronnie Moore's name

as Moo-er. |

| |

| I also knew the names of a number of the

leading speedway riders through conversations in the house between

my father and brother and I would pretend to be one of them when

out on my bike, cycling round our local park, in particular Split

Waterman and Aub Lawson, as they sounded very romantic to me. |

| |

| Sadly, by the time I was deemed old

enough to go to speedway, all the London tracks bar Wimbledon had

closed down and that was a bit too far away from our Hackney home,

so I didn't actually get to see my first meeting until 11 May

1960. The year before, 1959, Johnnie Hoskins had revived New Cross

and had put on a series of open meetings. In 1960, New Cross

resumed its place in the old National League. On his way home from

work every evening, Dad used to buy a copy of the Evening News. On

Mondays and Wednesdays they would print details of that evening's

meetings at Wimbledon

and New Cross, including a complete heat by heat programme |

| |

| And so it was, that on 11 May 1960, I

read about that night's meeting at New Cross, a Britannia Shield

match against Norwich. I asked my dad if we could go and, to

my great surprise, he said yes. When we arrived

at the track we bought a programme where I saw, to my utter

amazement, the first heat brought together my two boyhood heroes,

Split Waterman and Aub Lawson. |

| |

| Right from the start I was enthralled by

this sport and we became regulars at New Cross until it closed at

the end of the 1961 season. In 1962 we managed to get to a few

meetings at Rye House, then in 1963, New Cross re-opened as did

Hackney, which was great for me, as the track was only a 15 minute

walk from my home. Sadly New Cross folded permanently in 1963, but

the following year, West Ham opened and I became a two tracks a

week man, visiting Hackney and West Ham regularly. I also started

to make the longer trek to Wimbledon when there was anything good

on there, so many weeks I went to speedway three times. |

| |

| I continued going as often as I could

and in 1999 I managed to persuade The History Press to publish a

book on speedway – Speedway in East Anglia - which is another

story in itself that I’ll recount separately.**see

below |

| |

| Although I can’t get along as regularly

these days, my love affair with speedway has continued now for

over 50 years as there is no doubt it is the greatest sport in the

world. |

| |

| ** Norman's Literary Prowess described

in his own words: - |

| |

|

In the introductory piece at the top of my

first page I said I would recount the story of how the History

Press came to publish my first book on speedway, so here goes. |

| |

|

Actually, just to be precise, it wasn’t

exactly the History Press who published my first speedway book it

was a company called Tempus Publishing, who later merged with a

couple of other companies to form the History Press. With that in

mind, here is the story. |

| |

|

By 1999 I had had a few books on local

history published by a few different publishers, and in 1998,

Tempus Publishing asked me to write a book for their series,

“Images of England”. Tempus were a very well known publisher in

the local history field, so it was something of an honour for them

to ask me to write a book for them. I finished the book a few

months later at the beginning of 1999 and decided to take my

manuscript and illustrations to their head office in Stroud in

Gloucestershire. I didn’t have to, I could have just posted it off

as I had mostly done with my other books, but I thought it would

be interesting to pay this leading publisher a visit in person. |

| |

|

On my arrival, I saw the editor who would be

handling my book and he offered to show me round the complex. On

my walk round I saw a number of sports books lying around which

surprised me a bit as I hadn’t realised Tempus dealt in sports

books. I said as much to the editor and he replied that as the

publishers of local history books they saw sport as part of the

local history of a place. He said they didn’t go in for publishing

general histories of sport or histories of big football clubs like

Arsenal or Manchester United but rather those of smaller towns

like Stockport or Rochdale for example as they were part of the

social fabric of the town. |

| |

|

I noticed a number of football books as well

as rugby league and cricket, so I said to him, “Have you ever

thought of publishing a book on speedway?” At that time there were

very few speedway books on the general market and those there were

were generally year books or magazine type books. As far as I knew

there were no real histories of individual clubs being published.

He gave me a funny look and asked me what speedway was! I

explained it to him and he asked if there were many followers. I

said there were something like 30 tracks up and down the country

with devoted followers. |

| |

|

He thought about this for a little while and then said, “I don’t

think we could sell enough books on the history of a single track

to make it worth while. It is just possible we might be able to do

a book on the history of a region. What do you think about that?”

I said, “Well anything that gets a speedway book published is ok

by me. I could do one on London with no problem.” He asked me how

many tracks were still operating in London. I replied, “None.” He

sucked his teeth and said, “That’s no good. I would see sales

being mainly at the tracks themselves not in town bookshops.” So I

said, “What about East Anglia then? There are still four tracks

operating there.” |

| |

|

He had another think and said, “Ok

then, I’ll give it a go. You write a book about the history of

speedway in East Anglia and we’ll publish it. How’s that?”

Delighted with my morning’s work I shook his hand and we had a

deal.

|

| |

|

Later that year I delivered the

manuscript and Tempus published 1200 copies. Less than two weeks

later, the editor rang me to say they had sold out. He said they

were printing 1200 more. They too sold out and by then end of the

third month they were into their third print run. |

| |

|

He rang me again and said the senior

management at Tempus couldn’t believe it as my book on Speedway in

East Anglia had sold faster than all their other sports books and

they said they hadn’t realised what a goldmine there was in

speedway and that they couldn’t get enough of them now. What also

surprised him was the fact that the books were selling in town

book shops rather than at the tracks, in particular in Norwich,

where there was no track at all. He asked me if I would like to go

ahead with my original idea of Speedway in London, which, of

course, became my second book. I also advised him to contact Jim

Henry and Ian Moultray as I thought they would like to do a book

on Speedway in Scotland and Robert Bamford, who I felt would do

one on Speedway in the Thames Valley area. |

| |

|

Speedway in London reached no. 3 in the

Sunday Times Sports Book charts and was another big success,

though it didn’t quite sell as many as Speedway in East Anglia,

which remained the top selling speedway book in the UK for another

five years until overtaken by Sam Ermolenko’s Breaking the Limits.

But then Sam did visit every track in the country flogging it! |

| |

|

After this, Tempus published not only

regional books, but also one club books. I myself had books on

Norwich, Wembley, Rye House, Eastbourne, New Cross and Crystal

Palace published, while others were published on Bristol, Swindon,

Southampton and many others along with biographies, e.g., Tom

Farndon, and autobiographies, like Sam’s book. There were also the

sort of general histories, such as Homes of British Speedway and

History of the World Championship, that Tempus said they would

never do! |

| |

|

For a while Tempus were churning

out speedway books like there was no tomorrow having found a niche

market. However, other publishers began to muscle in and there was

a big upsurge in the number of speedway books being published from

one or two a year to dozens of them. Something for speedway fans

who had been neglected for far too long to get their teeth into.

And I like to think it all started with my visit to Tempus’s

headquarters. |

| |

| Some of my books: - |

| |

|

| Book Covers Courtesy of Norman Jacobs |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| The Origins Of Speedway |

| |

(By Norman Jacobs)

|

The Origins of Speedway

There is an old philosophical paradox that goes, “All that is

certain is that nothing is certain.”

There is no doubt this applies to the origins of speedway.

The first problem we have is what do we mean by speedway? Is it

just motor bikes racing round a small oval track or does the

definition of speedway include no brakes and sliding round the

corners on a loose surface?Certainly if we just take the meaning as motor bikes racing round

a small oval track there can be many claimants to the title of the

first speedway meeting in the world. There are reports of this

activity taking place in America in 1901, in

Ireland

in 1902, in Australia

in 1904, in South Africa

in 1907 and in Prague

in 1908 amongst many others.

Even if we add the no brakes and sliding

round corners ingredients, there is ample evidence to show that

American riders were broadsiding round dirt tracks well before the

First World War. A rider called Don Johns who started around 1909

and won the National Dirt Track Championship in

Chicago in 1912 may have been the first. A

contemporary description of him goes like this, “Don Johns

preferred to barnstorm the 1-mile dirt track circuits of California and the Midwest,

gaining experience as well as a reputation as the hardest fighting

rider in the no-holds-barred game. By 1914, Johns had improved to

such an extent that the Excelsior could not hold him. He would

ride the entire race course wide open, throwing great showers of

dirt into the air at each turn.” How else could you throw great

showers of dirt into the air on the bends if not by sliding? Was

Johns the first speedway rider in the world?

He was followed shortly afterwards by another

American called Albert “Shrimp” Burns who was killed in a track

crash on 14 August 1921. Part of his obituary written by C.E.B.

Clement, which appeared in Motorcycle and Bicycle Illustrated

reads, “I strolled down the track to watch him take the turns.

Here he came with that motor humming a great tune and into the

turn he went. Watching him handle that machine in the long slide

all the way around, I saw in fancy, the then great battler of the

day, Don Johns.For Burns was holding the pole and fighting the

rear wheel in a manner that very closely resembled the work of the

then known hardest fighter of the racing game."

After the War, in the late teens and early

twenties, two more Americans, Maldwyn Jones and Eddie Brinck, were

renowned for the way they threw their bikes in to the bends and

broadsided round, using what was known as the pendulum skid.

By the early 1920s Australia had also discovered the

sport of motor cycles racing round small oval circuits. The

generally accepted wisdom used to be that Johnnie Hoskins

“invented” speedway at Maitland Showground in 1923. Evidence from

America clearly shows that this is not the case, and, even in

Australia there are many reports of meetings similar to that put

on by Hoskins prior to 1923 in places such as Townsville (as early

as 1916), Rockhampton and Newcastle. Eleven months prior to

Hoskins’ much vaunted December 1923 carnival on the grass track at

Maitland, motor cycles had raced on a cinder circuit under lights

at Adelaide’s

Thebarton Oval. Again, in the Adelaide Mail, dated 3 November

1923, there is an article headlined, “Steering into a skid Dirt

Track Methods”. This article goes on to say:

“To steer away

from the direction in which a corner is being taken is quite a

usual practice on level tracks with a soft surface…it appears to

be voluntarily adopted by the experts in order to make the turn at

a higher speed than would be possible in the ordinary way…On a

dirt track the friction available is very small, consequently in

order to corner without skidding, a very low speed would be

necessitated..” So there we have an article explaining the process

by which the “experts” take the corners on dirt tracks over one

month before the meeting at Johnny Hoskins’ meeting at West

Maitland. Indeed, the major argument against speedway

originating on 15 December 1923 at Maitland is the Monday December

17, 1923 Maitland Daily Mercury's report on the Saturday December

15 carnival, which says: -

"For the first time motor cycle

racing was introduced into the programme and the innovation proved

most successful. In an exhibition ride at the last sports several

riders gave the track a good test and they then expressed

themselves satisfied with it. They also stated that it was better

than several other tracks that have been used for this kind of

sport on a number of occasions..." Note that last sentence in

particular. Maitland’s own paper did not see the meeting on 15

December as anything new. The riders themselves were comparing

Maitland to “several other tracks”

Perhaps the boost Maitland did give to the

sport however was to provide speedway on a regular basis as

between 15 December 1923 and 26 April 1924 there were no fewer

than 15 carnival meetings featuring motor cycle racing., with

promoters Campbell and DuFrocq staging six of them and including a

rider by the name of Charlie Datson who was to become one of the

leading pioneers of the new sport of speedway.

By the mid 20s a number of tracks were

presenting motor cycle racing round small oval tracks on a regular

basis. An article describing racing at Newcastle during the 1925-6

season says, "... these machines took the turns by running into

broadside skids ..." while "In the semi-final of the A Grade match

Lamont beat C. Datson after a remarkable exhibition of broadside

skidding around the turns" appears in a meeting report from the

Sydney Showground in August of 1926. By then it would seem that speedway more or

less as we know it today became established and continue to evolve

to the sport we all know and love today. |

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| The Origins of Speedway in GB |

| |

| (By Norman Jacobs) |

| |

The Origins of Speedway in

Great Britain

As with the origins of the sport

worldwide, the origin of Speedway in Great Britain is not clear cut

either. What is considered by many to be the first speedway

meeting in this country was held on 19 February 1928 at High

Beech, but this is disputed by advocates of Droyslden and

Camberley, both of which are said to have held meetings in 1927.

In fact, if we look back in to the mists of

time, Britain also has

its claimants to the first meeting to be held in the world. There

are reports of motor cycles racing round small oval tracks from

many places including Preston Park (Brighton) 1901, Shepherd’s

Bush (London), 1902 and Ipswich, 1904, but none of these would

have been remotely like speedway as we understand it today.

Certainly by 1927, motor cycle enthusiasts in Great Britain would have been aware of events

taking place in America

and Australia.

Lionel Wills, a Cambridge

undergraduate and keen motorcyclist, visited

Australia

in 1926 and witnessed speedway first hand at the Sydney Royale

track where he saw Charlie Datson and others flinging their bikes

round the corners at impossible angles. He was so enthused by what

he saw that he asked Johnnie Hoskins, the promoter at Sydney

Royale, if he could have a go himself. It is not clear if he

actually did have a go himself but if he did he would probably

have become the first domiciled Briton ever to ride proper

speedway. After his first outing he wrote home to the motor cycle

press in this country describing his own riding experiences and

recounting the hair-raising exploits of the likes of Datson, Paddy

Dean, ‘Cyclone’ Billy Lamont and the American, Sprouts Elder,

urging clubs to take up the sport. In addition, on discovering

Wills was British, Hoskins told him that he hoped to bring

speedway to Great Britain

and the two of them discussed how this might be effected.

Following Wills’s visit in 1926, two more

Britons arrived in Australia in 1927, Captain Olliver and Captain

Geoffrey Malins who were undertaking a round the world motorcycle

trip sponsored by motor cycle manufacturers, C.F. Temple Motors to

publicise their new Temple OEC sidecar outfits.

On the evening of their arrivalthere was

a public dress rehearsal at A J Hunting’s new Davies Park track in

Brisbane in preparation for its official opening later in the

week. A J Hunting was, by now, probably the leading

promoter of this new sport and DaviesPark was a purpose built

loose surface quarter mile track with grandstands, floodlighting

and a regular schedule of meetings. Many of the leading names of

the early days took part in the meetings at DaviesPark

including Vic Huxley, Frank Arthur, Billy Lamont, Dick Smythe and

Charlie Spinks.

Olliver and Malins

would almost certainly have paid DaviesPark a visit as the dress rehearsal was a big occasion

in Brisbane. According

to the magazine, “Motor Cycling”, it was after seeing these top

riders in first class surroundings that Olliver cabled his

brother-in-law, Jimmy Baxter, who was the managing director of

TempleMotors, saying that speedway was making big money in Australia and he felt sure it might do the same

in Britain

if organised properly. Baxter then got in touch with the

Australian promoter Keith McKay. McKay had tried his hand at

racing but had not been very successful. Instead he turned to

promoting and had been responsible for the introduction of

speedway at the very successful Wayville Show Grounds in Adelaide, so Baxter contacted him to discuss how speedway

might be brought to

Great Britain.

In addition to

Wills and the two Captains, another Briton, Stanley

Glanfield, arrived in Brisbane on 16

December 1927 as part of a planned round the world trip undertaken

from the premises of his own business, Glanfield Lawrence

Motors Ltd., in Tottenham Court Road in London.

On the evening of the 17th, Glanfield was a guest of

Hunting’s at Davies Park where he had his first sight of

speedway. Like Wills,

Olliver and Malins before him, Glanfield found this new sport

breathtaking. He was just one of a record crowd which was present

at Davies Park that night to see riders including Vic Huxley,

Frank Arthur, Frank Pearce, Dick Smythe, Billy Lamont, Charlie

Spinks and Sprouts Elder in action.In the Brisbane press the following day,

Glanfield is reported as having made the following comment, “In

England, where motorcycling has become a national pastime, a

programme such as I have seen here tonight would draw crowds of

50,000 or more regularly.” Glanfield also stated that such a

thrilling and exciting sport had never been dreamed of in Britain

where track racing was practically confined to the concrete at

Brooklands.In fact so moved was Glanfield that the

following day he penned a letter to A J Hunting telling him how

exciting he found the whole thing. At one point in the letter he

says, “I believe you intend introducing dirt track racing in

England. Let me assure you that it would be an unqualified

success, providing, of course, you are fortunate enough to find

convenient and suitable accommodation.”This is an interesting statement as it

shows that Hunting must have already announced plans to this

effect.With all these reports filtering back to

this country of an exciting new sport taking place in Australia,

interest was growing in staging a meeting in Great Britain. The

first attempt was made by the Camberley Club on 7 May 1927, who

staged a meeting on Camberley Heath in Surrey on a 440 yard track.

The leading rider at this meeting was C Harman, who won both the

350 cc and the 500 cc events. Another rider at the meeting was

famous female motor cycle racer, Fay Taylour. Camberley is generally discounted today as

the first real speedway meeting in Britain because the course was

rough and consisted of sand which was too loose and deep for

sliding and because competitors raced the wrong way round, i.e.,

clockwise.

The next club to enter the fray was the South

Manchester Motor Club. One of their members, Harrison Gill,

organised a dirt track meeting at a place known as Moorside

Stadium on Dodd’s Farm in Droylsden on 25 June 1927. The track was

probably 600 yards long, although there is no precise record of

how long it was. This time instead of the surface being too deep,

the cinders on the track were packed down hard leaving no loose

dirt at all. Eight hundred spectators witnessed the event. The

first race was won by local motor cycle dealer, Fred Fearnley,

while the winner of the “Experts’ Race” was Charlie Pashley

The most successful rider of the day, however, was Ron

Caves, who managed to win two events.

Both the Camberley and Droyslden events were

“amateurish” affairs staged by people who had probably never seen

real speedway and were going by the reports sent back from

Australia and America. In addition to the fact that the track

surfaces were not conducive to broadsiding anyway the Auto Cycle

Union (ACU) insisted that the motor bikes used be fitted with rear

brakes and in any case the riders thought it unethical to touch

the ground with their feet. If we take our definition of speedway

to be sliding round loose surface tracks, they can safely be

discounted.

Towards the end of 1927, Lionel Wills, who

had by now returned to Great Britain, made a concerted effort to

obtain support for the staging of a proper speedway meeting as he

had seen it at Sydney. Amongst those he tried to persuade were

Fred Mockford and Cecil Smith, who at that time were organising

Path Racing on a mile long circuit around the gravel pathways of

Crystal Palace and put Johnnie Hoskins in touch with them. Wills

himself was a regular performer at these races along with others

who would one day make a name for themselves on the speedway,

including Gus Kuhn, Joe Francis and Triss Sharp.

But it was Jack Hill-Bailey, honorary

secretary of the Ilford Motor Cycle and Light Car Club, who was so

enthused by Wills’ articles that he became the first to take

practical steps to organise a proper speedway meeting in this

country. His first proposal was to organise a meeting on a half

mile trotting track in Ilford called Parsloes Park, which was

owned by the London County Council (LCC). Hill-Bailey asked the

Ilford Club’s president, Sir Frederick Wise, the MP for Ilford, to

conduct negotiations with the LCC. Sadly, just as the negotiations

got underway, Sir Frederick died and the discussions were put on

hold.

Hill-Bailey then looked around for another

site and found what he considered to be the ideal site, a disused

cycle track at the back of the King’s Oak Public House in Epping

Forest near Loughton at a place called High Beech. He was granted

permission by the owners to convert the cycle track into a

speedway track and then applied to the ACU for permission to run a

meeting on 9 November 1927. Hill-Bailey was a good friend of Jimmy

Baxter’s and was therefore aware that Baxter was also interested

in introducing speedway to this country. Consequently, he reached

an agreement with him for the meeting to be jointly organised by

his own Ilford Club and Baxter’s Metropolis Club, one of the

largest motor cycle clubs in the country, and of which Baxter was

president. The ACU turned down the proposal on the grounds that 9

November was a Sunday. However, they added that if a new

application was made asking permission for a closed meeting, that

is one restricted to club members only, they would grant it.

Consequently Hill-Bailey reapplied for permission to run a closed

meeting on what has probably become the most famous date in

British speedway history, 19 February 1928. After a three hour

inspection by four ACU officials who included prominent motor

cycle racer and future Wembley captain, Colin Watson, permission

was granted.

In the meantime, Baxter’s Australian contact,

Keith McKay, set sail for England on the

SSOronsay on 10 December 1927 to join up with him as promoter and

director of a new company dedicated to promoting speedway, Dirt

Track Speedways Ltd. While on board the Oronsay, McKay met up with

another speedway rider, Billy Galloway, who was working his

passage as the ship’s barber. It is not known for certain whether

Galloway knew about plans for the introduction of speedway in

Britain or whether his involvement just came about by a chance

meeting with McKay on board the Oronsay. Whatever the reason for

his being on board the Oronsay, Galloway joined McKay and they

both went to see Baxter on their arrival.

Although no longer

involved as joint promoter, Baxter was still taking a prominent

role in the organisation of the High Beech meeting and as a

precursor to it, he arranged for McKay and Galloway to give a

demonstration of the art of real speedway at Stamford Bridge, the

home of Chelsea Football Club, early in 1928. This demonstration

was filmed by Pathe News and must certainly have been the first

time proper speedway was seen in this country. It is probable that

this film, being a Pathe News feature, would have been shown in

cinemas around the country and certainly in London, thus giving a

massive publicity boost to the High Beech meeting and could

explain why so many people turned up on that cold February day in

1928 to witness what is now generally accepted as the first

speedway meeting in Great Britain. Hill-Bailey had planned for

around 2000 spectators but in fact over 20,000 attended.

Two of the riders

at this meeting were, of course, the Australian pair, McKay and

Galloway, and one of the officials was Jimmy Baxter. One of the

prominent English riders to take part was Alf Medcalf, vice

chairman of the Colchester Motor Cycle Club. And in fact, although

Hill-Bailey was the driving force behind it, the meeting was

jointly organised by his own Ilford Club and Medcalf’s Colchester

Club, whose club President, Ernie Bass, was another of the

officials at the meeting. Incidentally, while Baxter and Bass

officiated, Lionel Wills was content to take on the job of track

raker.

Although generally

accepted as the first speedway meeting in Britain, it was, in

fact, little different to the Droyslden meeting in that the

surface was hard packed and sliding was impossible and, in any

case, as before, the ACU ruled that the bikes had to be fitted

with rear wheel brakes and most riders still considered it wrong

to put their foot on the ground, although there is photographic

evidence to show that some at least did touch the track with their

foot. In addition to this, all the riders, apart from McKay and

Galloway, had never seen speedway before so were unsure what they

were supposed to do and the brakes were used often and violently

as the uninitiated tried their best to race round the small

circuit. When Galloway came out for his first race he got off to a

bad start as his engine cut out entering the second bend, causing

him to drop back to last place. Getting over this temporary

problem, he opened the throttle full out and swept in to the third

bend but instead of broadsiding he went in to a series of

spectacular skids. Eventually his greater experience told and he

passed the others to take the chequered flag in first place.

However, much to Hill-Bailey’s disappointment as he had been

expecting Galloway and McKay to demonstrate just what a

spectacular sport speedway was, Galloway had won the race without

once actually putting his foot down. He explained afterwards that

the surface was not suitable for sliding. He had been used to the

loose surface of the Australian dirt tracks but High Beech was a

hard rolled cinder track. Another big handicap for him was that he

was unable to use his own bike and instead had to borrow Freddie

Dixon’s Isle of Man TT machine with road racing gearing and he

never worked out how to get out of bottom gear.

In all forty two

riders took part in the day’s events on their own road or trials

bikes. Some riders made the effort to strip off unwanted items,

but other didn’t even do that, racing with their lamps, horns and

speedometers still in place. The very first race on that

auspicious day was the heat one of the Ilford Novice Event and was

won by Mr A Barker on his Ariel. However, given the importance of

that race to the history of speedway it was a complete anti climax

as Mr Barker was the only competitor in the event and he tootled

round sedately more concerned with not falling off and reaching

the finishing line than with giving a demonstration of racing.

Meanwhile, Hunting

had set sail for Great Britain on 23 January and probably because

he had heard about the High Beech meeting left the ship at Naples

and continued his journey overland so that he could arrive in time

for the meeting as his ship was not due to dock in London until 23

February, four days too late. He eventually arrived midway through

after a dash to the track by taxi. Although the meeting itself was

a big success, Hunting, who knew how it should have been run, was

less than impressed. He sought Hill-Bailey out and said to him,

“My boy you’re all wrong – this isn’t the way to run a dirt track

meeting.” He explained to Hill-Bailey how the track should be

redesigned and suggested several other improvements including the

need for a good wire safety fence.

It is probable that

because the likes of Wills and McKay had been involved in the

organisation Hill-Bailey already knew this to be true, but he had

been hamstrung a) by the lack of funds to do what he knew should

have been done and b) the ACU’s insistence on rear brakes. To

overcome the first problem, the Ilford Club made a financial

appeal to two well-known wealthy supporters of motor cycle racing,

Alderman F D Smith and W J (Bill) Cearns, head of The Structural

Engineering Company, a large engineering firm in nearby Stratford.

Cearns agreed to carry out the work needed for nothing and by 29

March, The Motor Cycle

was able to report, “Considerable strides have been made in the

reconstruction of the King’s Oak Speedway in High Beech, Loughton

and the track will be ready for practising on Saturday. The width

of the track has been increased to 40 ft on the bends and 30 ft on

the straights, and later there are to be concrete terraces and a

grandstand for spectators. Three meetings have been arranged.”

The first meeting

to be held on this new track took place on 7 April 1928, Easter

Saturday, and was probably the meeting that

The Motor Cycle referred

to when it said “the track will be ready for practising”. There

are no detailed reports of this meeting as the main meeting was

the one held on 9 April, Easter Monday, or rather the two

meetings, as there was one in the morning and one in the

afternoon.

This time the track

surface had loose dirt and the ACU had lifted their embargo on

rear brakes and so, it is likely that, for the first time in this

country real speedway was seen in a competitive setting.

Headlining its report, “Spectacular Racing Before Big Crowds at

the Reconstructed King’s Oak Speedway, Loughton!”,

The Motor Cycle went on

to say, “Thrills! Thrills! Thrills! 17,000 spectators at the

King’s Oak Speedway, Loughton, had a full quota of them on Monday

when the Ilford Club staged a dirt-track meeting on a track which

is a marvellous improvement on the one used at the first event

nearly two months ago.” Three riders were able to demonstrate the

art of broadsiding on the loose dirt surface, Colin Watson, Alf

Medcalf and the enigmatic, Digger Pugh. Digger Pugh was a bit of a

mysterious character who had turned up at High Beech a short while

earlier claiming to be a speedway rider of some renown from

Australia and offered to school the British riders in the art.

Hill-Bailey appointed him as coach and machine examiner. The fact

of the matter is however that Digger Pugh had no pedigree as a

rider in Australia at all and it is doubtful if he had even been

in Australia since speedway had started there. Whatever his

background, he was able to perform himself and was responsible for

training up some of the best of the early British riders like

Watson and Medcalf and also Roger Frogley,

Although it is

likely that the two meetings on 9 April saw the first real

speedway in this country, it should be mentioned that, on 3 March,

the South Manchester Motor Club held another meeting, this time at

Audenshaw with McKay and Galloway taking part. Once again a large

crowd of something like 20,000 turned up to see the two

Australians as well as the first appearance on a small motor cycle

track of riders of the calibre of H R “Ginger” Lees, Alec Jackson,

Bob Harrison and “Acorn” Dobson. Once again it must be doubted

whether it was real speedway as we know it as firstly the track

was just over half a mile long and secondly, as McKay himself

complained, the track had no loose dirt on it so broadsiding was

not possible. And then, on 7 April, Greenford held its first dirt

track meeting. Again it was a half mile track, although one of the

organisers, Mr Frank Longman, felt it was ideal for broadsiding.

The racing was dominated by Billy Galloway, but it seems that not

even he actually did any broadsiding, leaving the 9 April High

Beech meetings as the most likely claimant to the first real

speedway seen in this country.

After these

pioneering events, the Australians began to arrive. Hunting had

already arranged for most of his top stars to come to Britain and

on 10 April 1928, the SS Oronsay left its final port of call in

Australia when it set sail from Freemantle with riders of the

calibre of Vic Huxley, Frank Arthur, Frank Pearce, Charlie Spinks

and Dick Smythe on board. Also on board was the other well-known

promoter, Johnnie Hoskins, with his riders, Ron Johnson, Charlie

Datson and Sig Schlam. Hunting had already been in talks with the

GRA and had taken out leases on Harringay, Wimbledon, London White

City and Hall Green (Birmingham) to operate speedway, while

Hoskins was headed for Crystal Palace where, following Lionel

Wills’ introduction, he had agreed to act as advisor to Fred

Mockford and Cecil Smith who were planning to open their new track

on 19 May.

With the arrival of

these Australian stars in May and some of the major London tracks

starting operations that month, speedway took off in a big way and

it was probably Hunting’s organisation, International Speedways

Limited (ISL), that set the standard for the future of speedway in

this country. As well as having the best riders and some of the

leading stadia, ISL also organised the leading events in the

country such as The Gold Helmet and also set up the first

dedicated speedway magazine, Speedway News, under the editorship

of Norman Pritchard who had been Hunting’s publicity officer at

Davies Park.

Although ISL took

speedway to new heights in Great Britain during 1928 it was

probably the introduction of league speedway the following year

that had the most lasting effect and turned speedway in to the

sport we really know it as today. It is said that the brains

behind league speedway was Jimmy Baxter, but the only thing

certain about that statement is that it is not certain…but that’s

another story… |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| Archie Windmill’s Finest Moment |

| |

| By Norman Jacobs |

| |

|

| |

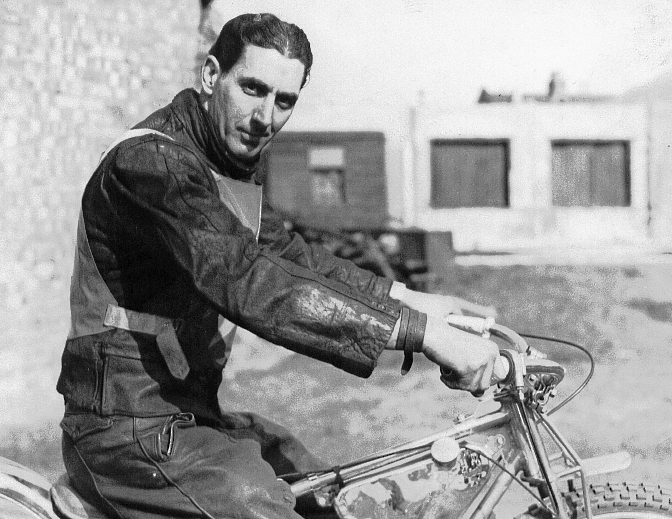

| Never one of the top stars, Archie

Windmill was always a never give up trier, who helped form the

backbone of the Wimbledon team in the late 40s Norman Parker era.

He was also one of the tallest riders ever to appear in British

speedway and was referred to by speedway journalist, Basil Storey,

as the ‘long-legged, poker-faced, imperturbable Windmill’. |

| |

| Archie’s greatest moment probably came in

the National League match between Wembley and Wimbledon held on 8

May 1947. He was already having a good night, having beaten the

Wembley captain, Bill Kitchen, in heat 4 and coming in second

behind his partner, Norman Parker, in Heat 9. In spite of Archie’s

sterling efforts however, the Dons were eight points down after

heat 11 with just three heats to go. Archie was due out in two of

those heats, 12 and 13, and despite Basil Storey’s description of

him, Archie said later that he was feeling very perturbed at this

point. Out he came in heat 12, once again partnering Parker and

once again amazingly recording a 5-1, thus reducing the deficit to

four points. |

| |

| With just a short break he was out again

in the next heat, this time up against the great Split Waterman,

but with Lloyd Goffe as his partner. Goffe had injured his wrist

earlier in the meeting and was not 100% fit. Nevertheless, Archie

saw him round to yet another 5-1, drawing level with Wembley. With

11 paid 12 points, Archie had scored an amazing maximum against

the team that completely dominated British speedway in the late

40s. Not only that but he had done it in the heart of the Lions’

den, the Empire Stadium itself. |

| |

| With the scores now at 39-39 there was one

more heat to come. This saw Wembley’s Bob Wells and Bronco Dixon

up against the Dons’ Cyril Brine and Dick Harris. With Archie

cheering his team mates on from the pit rails, this last heat

turned out to be rather eventful as Wells fell at the first bend,

and then, in his excitement, Harris crossed the white line and was

disqualified. This left just Dixon and Brine to battle it out.

Brine was in the lead but Dixon was snapping away at his rear tyre

the whole way. On the last bend Dixon swept round the outside but

Brine just managed to hold him off for the 3 points and a single

point victory for the Dons over the mighty Lions. |

| |

| Although there was no doubt it was a team

effort, it was Archie who had won the two vital heats to ensure

victory. Eight points behind after heat 11, Archie’s two wins

provided the chance Cyril Brine took with both hands. |

| |

| Archie said afterwards that that meeting

provided his greatest thrill in speedway |

| |

| Another Photo of Archie |

| |

|

| Archie Windmill in Walthamstow Wolves

colours - Photo Courtesy of J Spoor |

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

An Interview

With The Late

Nobby

Stock |

By Norman Jacobs |

| |

|

| |

|

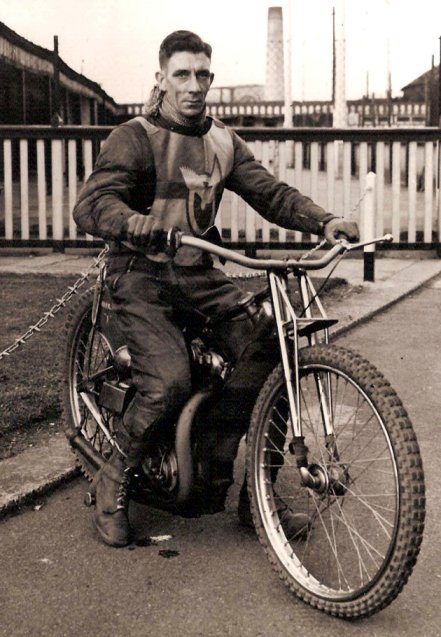

Nobby Stock rode for Hackney and Dagenham before the

War and for Harringay, Bristol and Ipswich after. He was never

what you might call a superstar but was always a first class team

man and an excellent second string; one of the unsung heroes of

speedway, without whom the sport could not exist. I once asked a

former Harringay supporter who he would select as his all-time

‘fantasy’ Harringay team. Without hesitation he pencilled in Nobby

in the no. 2 position. |

| |

|

When I was carrying out research for my book,

Speedway in London, I

visited Nobby at his home in Clacton-on-Sea to talk about his days

at Harringay. I was hoping that this would be just the first of a

number of visits but sadly Nobby died not long after I met him.

So, as a tribute to Nobby, although our discussion was only really

a preliminary one and not as in depth as it would have

been had I known it was going to be my last chance to speak

to him, I thought it would be worth as there are one or two

interesting facts and little snippets that had probably not been

published before. |

| |

|

| Nobby Stock - Photo Courtesy of J Spoor |

| |

|

NJ: How did you first get in to speedway? |

|

NS: I lived in Rainham in Essex, just round the corner

from Frank Hodgson, the Dagenham and Hackney captain. I used to

help his mechanic clean his bike. When I was 11 I bought a belt

driven Raleigh for 1/- and raced it on the village green at

Rainham. Some of the other boys and I made our own track by

clearing the grass away and making a cycle speedway circuit. I was

also a member of the West Ham Supporters’ Club. If you were a

member it cost you 7d to get in instead of the normal admission

price of 1/2d. Johnnie Hoskins was a great showman of course and

made the whole evening worth the money. In the interval he used to

arrange camel races, hoop races for kids, horses v. motor cycle

races and so on. |

| |

|

NJ: When did you first graduate to the real thing

yourself? |

|

NS: When Arthur Warwick started his speedway school at

Dagenham I went along to have a go. I spent all my savings on a

bike. The bike had originally been Eric Chitty’s and I got it for

£70. As well as Dagenham I had a few rides at Smallford, Arlington

and Rye House. And then in 1938 I signed for Hackney. Of course

just as I was starting to make a name for myself the War came

along and put a stop to speedway racing in England. |

| |

|

NJ: I believe you managed to race out in Italy during

the War. |

|

NS: Yes. I was responsible for organising Army Speedway

Racing in Italy and helped build a number of tracks out there. I

raced at Trani, Bari, Molfetta and Naples. I won a number of

trophies. At one time I held all the track records at Naples

except the four lap flying start. One of my fellow racers out

there was Split Waterman. |

| |

|

NJ: What happened after you returned to England? |

|

NS: I was demobbed on 4 February 1947 and on the 5

February I received a telegram from Fred Whitehead and Fred Evans,

who had promoted speedway at Hackney before the War, asking me if

I could turn out for Harringay. I arrived for the opening meeting

on Good Friday and there was snow all

over the place. Anyway, I was signed up for the team and

told I would be partnering Vic Duggan. Most of the Harringay team

at that time were Australian. I felt quite lonely as an English

rider! The

following

season, 1948, I was loaned out to Bristol. I had one season there.

They wanted to keep me but Harringay recalled me for 1949. |

| |

|

NJ: What was it like partnering Vic Duggan? |

|

NS: Well you never asked Vic what starting position he

wanted as he always took one or two. He used to say to me, “You

get a good start, Nobby, and I’ll see you home.” But he never did!

But he did use to help out the other riders in the team

whenever he could. If there were four Harringay riders in the

scratch race final, Vic would inevitably win, but he would always

split the prize money

four ways. He was a great rider and it was such a disappointment

when he fell in the 1947 British Riders’ Final after completely

dominating the speedway scene that year. It was unheard of for Vic

to fall. |

| |

|

NJ: Were there any other characters in the Harringay

team? |

|

NS: Well, of course, Split Waterman was mad just like

Bruce Abernethy. I remember once George Kay and Wal Phillips took

us to Paris as a reward after we’d won a trophy – I can’t remember

what at the moment – but Bruce wanted to climb to the top of the

Eiffel Tower. Lloyd Goffe was another character. Every time he

rode he used to put cotton wool on the cheeks of his backside

because he sweated so much! |

| |

|

NJ: You left Harringay for Ipswich in 1953. What did

you think of Ipswich? |

|

NS: I wasn’t too keen on it because it was a big track.

I preferred small tracks. I used to ride better on small tracks or

wet tracks as they brought every else down to my speed! The best

night I ever had was at Wembley when I got 9 paid 11 out of 12. It

was raining that night! |

| |

|

NJ: Thank you Nobby. |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

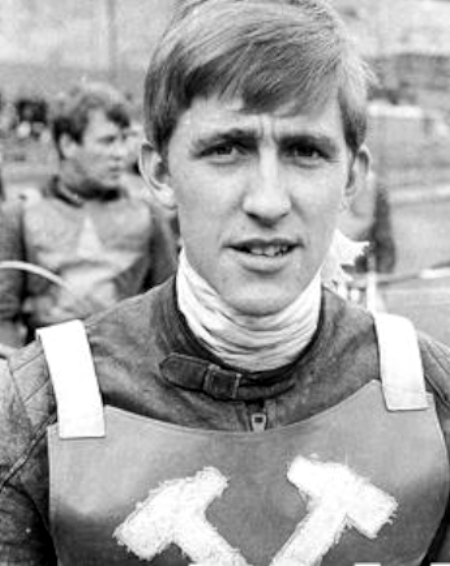

The Day Malcolm Simmons Became A Star!

|

|

By Norman Jacobs

|

|

|

|

|

Picture Courtesy of Norman Jacobs |

|

|

|

Malcolm Simmons |

|

|

|

The best meeting I ever

saw: The day Malcolm Simmons became a star! (Norman Jacobs

writes).

By 1965, with the demise

of New Cross two years earlier, I had become a confirmed West Ham

supporter, going regularly every week to Custom House plus quite a

few away matches. 1965 was the first year of the British League as

well as a new Knock Out Cup competition based on football’s F.A.

Cup with just one leg and the luck of the draw which team got

drawn at home.

Picture Courtesy of Norman Jacobs

West Ham 1965

In that year, one of the

Quarter Final matches saw a local derby London tie with West Ham

drawn at home to Wimbledon. Before the tie, the two teams appeared

to be evenly matched and so the match proved. With one heat to go

the scores were level at 45-45. That final heat saw the Wimbledon

pair, Olle Nygren and Reg Luckhurst, shoot in to an early lead

over West Ham’s Brian Leonard and Norman Hunter and it looked all

over for the Hammers when suddenly Luckhurst’s engine blew up

resulting in a 3-3 and a tied match at 48-48.

Having drawn at West

Ham, Wimbledon looked a good bet to take the tie in the replay on

their own track. But there was even worse news for West Ham as

their top rider, Sverre Harrfeldt, was injured the previous

evening at Hackney and unable to take part and their third heat

leader, Norman Hunter, was also unable to ride as it was his

wedding day!

There were no guests

allowed so the Hammers had to resort to filling the places of two

heat leaders with Tony Clarke, making his racing debut, and a

Wimbledon junior, Geoff Hughes. Only Ken McKinlay was a recognized

heat leader and, although by now a team regular, it should be

remembered that at this time West Ham’s 19 year old Malcolm

Simmons was just a reasonable five point average second string who

had shown no signs of the great rider he was to become in later

years. No-one, not even the West Ham supporters present that

afternoon, gave the Hammers much hope.

By heat six it looked as

though Wimbledon’s superiority was about to assert itself as

Wimbledon skipper, the great Olle Nygren. along with the

experienced Jim Tebby, took a 5-1 against West Ham’s newcomer,

Tony Clarke, and second string, Brian Leonard. The lack of two

heat leaders looked as though it was now beginning to tell.

But as West Ham were six

points in arrears it meant they could use a tactical substitute

and they wasted no time bringing in Ken McKinlay for reserve Ray

Wickett in the very next heat. The line-up for heat seven was

therefore Bob Dugard and Keith Whipp for the Dons, Malcolm Simmons

and Ken McKinlay for the Hammers.

The young Simmons shot

away from the gate with McKinlay behind him and that’s how the

heat finished. A 5-1 for West Ham and four points pulled back.

Simmons’ time of 66.2 was the fastest of the night.

The next heat saw

McKinlay out again, this time in a scheduled ride, with old

campaigner Reg Trott lining up against Reg Luckhurst and reserve

Mike Coomber. Some brilliant team riding by McKinlay and Trott

kept Luckhurst behind them and with Coomber falling, it meant

another 5-1 to the Hammers and, unbelievably, at the half-way

stage, West Ham now found themselves with a two point lead.

With Nygren and Tebby

lined up against Simmons and Wickett in heat 10 it looked as

though the Dons would edge back in to the lead, but, once again,

Simmons rose to the occasion and beat Nygren in the second fastest

time of the night. Heat 12 saw another astonishing turn of events

as Wimbledon’s Bobby Dugard fell and was excluded from the re-run.

It was a simple matter for McKinlay and Trott to defeat Whipp and

take a 5-1.

It was now West Ham who

were six points up and it was now Wimbledon who used a tactical

substitute as they brought in Nygren for reserve, John Edwards.

Unfortunately, it did not have the desired effect as, for the

second time that night, West Ham’s new hero, the young Malcolm

Simmons, beat Nygren, leaving West Ham still six points in front.

This time though, Simmons had done it the hard way, coming from

behind and taking the Wimbledon captain on the last lap.

With just three heats to

go, time was running out for Wimbledon and the impossible suddenly

looked possible. However, a Nygren and Dugard 5-1 over Trott and

Leonard put them back in with a chance and when, in heat 15, Tebby

and Coomber pulled off a 4-2 against Clarke and Hughes, the

scores, were back to level with one heat to go.

The line-up for that

final heat saw Keith Whipp and Reg Luckhurst for Wimbledon against

Ken McKinlay and Malcolm Simmons for West Ham. The tension around

the stadium was palpable. Everyone was holding their breath. A

match which at the beginning of the afternoon had seemed likely to

be very one-sided had now come down to a last heat decider.

To some extent the final

race as a race was a bit of a disappointment as Simmons once again

flew off from the start and never looked to be in any danger and

with McKinlay settling for a steady third place, the match was won

by West Ham by 49 points to 47.

The small band of

Hammers’ supporters who had made the trip across London couldn’t

believe what had happened. The hero of the hour was the 19 year

old Malcolm Simmons. He had beaten the Wimbledon captain, Olle

Nygren, twice and had set the three fastest times of the night. In

fact he still wasn’t finished.

In the second half

scratch race event, the Cheer Leaders’ Trophy, he won the first

heat, beating, McKinlay, Luckhurst and Dugard and then went on to

win the final, once again beating Nygren. As if that wasn’t

enough, a special Handicap race was held with Simmons starting off

20 yards, Nygren off 10 and Trott, Leonard and Tebby off scratch.

Yet again, Simmons got the better of Nygren, even with his

handicap.

As for me, although that

match was held 52 years ago I can still remember it as if it were

yesterday. In fact, I can remember it better than matches I saw

last season. It was just such an amazing afternoon. I went along

there with a few other Hammers’ supporters expecting a reasonable

match but when it was announced just before the

meeting started that

neither Harrfeldt nor Hunter would be taking part we seriously

considered going home. The Wimbledon supporters around us were

saying things like, ’You’ll be lucky if you get 20 points’ and

’This is going to be the biggest thrashing of all time.’ Of

course, we gave back as good as we got but in our hearts we felt

they could well be right.

But suddenly there was

this rider called Malcolm Simmons, who we had seen rise from the

ranks of a second halfer at West Ham to a reasonable five point

second string but no more, taking on and beating the likes of Olle

Nygren and Reg Luckhurst on their own track in the fastest times

of the night. He was just phenomenal.

Recalling the match

later in an interview I carried out with him, Malcolm Simmons said

that the West Ham team had gone to the meeting thinking they would

get thrashed but somehow the whole team had risen to the occasion.

He went on to say,“It was the first good meeting I ever had for

West Ham. I just came good on the night.”

As we now know, Simmons

went on to become one of Great Britain’s greatest ever riders and

runner-up in the 1976 World Championship, World Pairs Champion in

1976, 77 and 78, World Team Champion in 1973, 74, 75 and 77 and

British Champion in 1976. He was capped 80 times for England,

seven times for the British Lions (touring Australia), five times

for Great Britain and four times for the Rest of the World.

But it all started that

night and I feel very privileged to have been there to witness

what must have been one of the best matches of all time and one of

the most outstanding personal performances of all time.

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

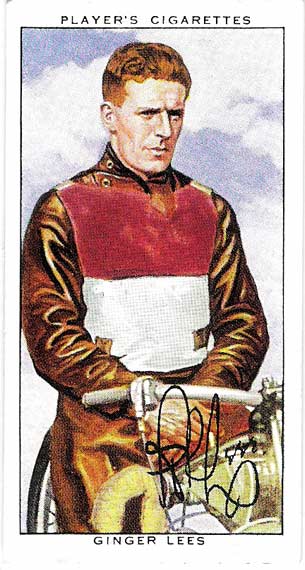

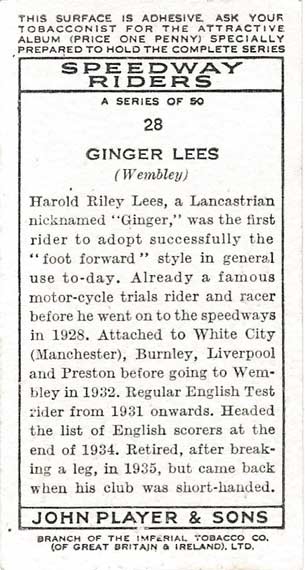

| Ginger Lees |

| |

|

By Norman Jacobs

|

| |

|

| Picture Courtesy of Norman Jacobs |

| |

|

Harold Riley “Ginger” Lees: Was he the first foot forward rider? |

| |

| It is said that Ginger Lees was the first

exponent of the foot forward style of riding anywhere in the

world. When the Australians and Americans brought the sport to

this country, they all used the spectacular leg trailing style.

However, Lees reasoned that if you didn’t have to lean your bike

so far over sideways entering a corner as all the leg-trailers had

to do, it would become upright much earlier leaving the bend and

so give more tyre traction. Instead of trailing his left leg

therefore, he pushed it forward on entering the bends. He did this

to such an exaggerated extent that, at times, it looked as though

he was standing over his bike. But it worked and this style of

riding was soon adopted by other top-class riders including Eric

Langton, Joe Abbott, Gus Kuhn and Wembley’s Harry Whitfield. |

| |

| So what do we know about him? Born in 1905

in Bury, Lancashire, Harry Riley Lees, known as “Ginger” because

of his thick shock of red hair, was one of the leading motor

cyclists from the North of England before the advent of speedway.

His first venture into competitive motor cycling was at the age of

14 when he took part in road racing, trials, rough riding events

and grass track racing. In 1927 he won the Gold Medal in the

International Six Days’ Trial, one of motor cycling’s premier

events, and, in 1928, he finished 19th in the Isle of

Man Junior TT race riding a New Imperial. |

| |

| When Audenshaw staged the first recognised

speedway meeting in

Manchester

on 3 March 1928, the spectators witnessed Lees, mounted on a

Rudge-Whitworth, sweep the board. He moved on to Manchester White

City and then, when league racing began in 1929, he signed up for

Burnley. |

| |

|

| Cigarette Card Courtesy of David Pipe |

| |

| He moved to Liverpool in 1930 and Preston

in 1931. By then, he had become one of the top English riders in

the sport and was chosen to ride for his country in the third

England

v. Australia Test match of 1931 at Wembley. Although he had never

seen the track before he won his first race and recorded the

fastest time of the night, just 3/5 of a second outside the track

record. |

| |

| Lees’ Test match debut did not go

unnoticed by the Wembley management and he was soon signed up for

the Lions by Johnnie Hoskins. He easily topped the Lions averages

in 1932 with a cma of 10.25. In 1933 he suffered from an ankle

injury and his average dropped to 8.99, though when he was fit he

still showed what he could do, scoring 54 points out of a possible

60 between 22 June and 13 July. He returned to the top of the

Wembley averages the following year with 9.88, but the following

year he broke his ankle in Wembley’s first League match of the

season. He made a brief return during the season and then retired

but was persuaded to make a comeback in 1936. Although his scoring

power was down on his best years, he still maintained an 8.00

average as the lions’ third heat leader, a position he maintained

in 1937, at the end of which season he finally retired for good. |

| |

| He was an automatic choice for

England

between 1931 and 1934 and at the end of 1934 he was England’s all-time top scorer. He

returned to ride for

England

in 1936 and 1937. At the end of his Test career he had ridden 21

times for England and

scored 197 points. He still holds the record for the highest

scores in individual Test matches, scoring 20 in the first Test

match of 1933 and 22 in the second Test. This was under the 4-2-1

scoring system. |

| |

| Lees reached the final stages of the Star

Championship in 1932 and again in 1934 when he finished third. He

also reached two World Championship finals, finishing 14th

in 1936 and ninth in 1937. |

| |

| He was very confident and self-assured

almost to the point of cockiness, but he could deliver when

challenged. One day at the Empire Pool, he was swimming with some

other Wembley riders when he boasted that he could do a swallow

dive off the top diving board. The others dared him to try. Lees

climbed up the tall ladder and made a dive an Olympic champion

would have been proud of. |

| |

| Perhaps a forgotten name these days, but

Lees was undoubtedly one of the pre-War greats of speedway and was

responsible for a style of riding that has served speedway well

for 90 years. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| Uncle Albert! |

| |

|

By Norman Jacobs

|

| |

|

In the late 1930s, my Uncle Albert became a

passionate speedway supporter. In the days when you could visit a

speedway track every night of the week in London he often did. But

his real heart was with Hackney Wick and some years ago I asked

him what his memories were of Hackney Wick. |

| |

|

Me: Which riders do you remember most from

your time going to Hackney Wick?

|

| Uncle Albert: I can remember Frank

Hodgson, who was the captain at one time, also Tommy Bateman, Doug

Wells, Jim Bayliss, he was killed in a motor accident in Australia

you know, Archie Windmill and Phil “Tiger” Hart. And there were

the reserves, Jack Tidbury, who had a Klondyke beard, Ken Brett,

Charlie Dugard and Nobby Stock also Bill Case. |

| |

| |

| Phil "Tiger" Hart |

| |

|

| Courtesy of Norman Jacobs |

| |

|

Me: What do you remember about them? |

| UA: I can remember that Phil Hart never

sat on his bike at the start, he would stand over it looking at

the release mechanism. When the tapes flew up he jumped on his

seat and flew off. His front wheel would invariably go up in the

air. Everyone knew him for this, for the way he started. Also Doug

Wells used to sit bolt upright like a soldier. He never crouched

over his bike. |

| |

|

Me: What about Frank Hodgson?

|

| UA: He was great. He never seemed to

lose at Hackney. He won everything. Doug Wells also very rarely

lost to the opposition. |

| |

|

Me: Archie Windmill was a good rider as well

wasn’t he? |

| UA: Actually, I wasn’t so keen on Archie

Windmill, I could take him or leave him. He had a very unusual

style. He stuck his left foot out well forward, and I mean well

forward, it seemed to reach out further than the bike. He never

seemed to bend it. There was one match though when we went to

Wembley to race in a charity match, a shield of some sort. I

didn’t go to it as I felt we were in for a right pasting away to a

big club like that. But the next day, the papers were full of it

and how Archie Windmill had scored a maximum! I couldn’t believe

it. I thought, he never gets a maximum at Hackney, how could he

get one at Wembley of all places? In spite of that we still lost,

though it was a much closer result than I thought it would be. |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

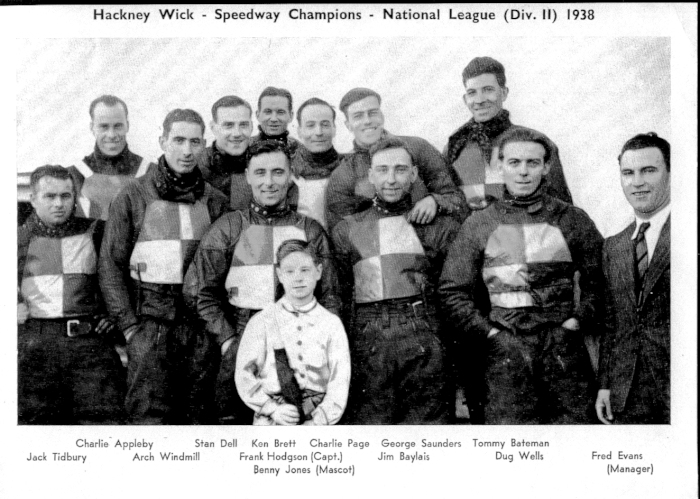

Hackney 1938 |

| |

|

| Courtesy of Norman Jacobs |

| |

| John says: Canadian Charlie Appleby was

killed in a crash at Brough Park Newcastle in 1946 when he was

riding for Birmingham. He was the 2nd fatality that year at

Brough Park! |

| |

|

Me: That was when Hackney Wick were in the

second division wasn’t it? |

| UA: Yes, I can remember seeing Bradford,

Nottingham and Leeds visit. I can remember the Nottingham match in

particular because of their star rider, George Greenwood. Now,

Doug Wells was a bit like Frank [Hodgson] at home and very rarely

lost a race, he was always miles in front of everyone else, but

George left him standing. We were absolutely amazed. |

| |

|

Me: Hackney were also in the First Division

at one time weren’t they? |

| UA: Oh yes, that was when Dicky Case was

the captain. He was very big, like an elephant! He left to go to

Rye House to become their manager as well as a rider. |

| |

|

Me: Did you ever go to away matches? |

| UA: I went all the time to the other

London tracks. I can remember New Cross in particular. It was only

260 yards, it was like going round in a circle. Georgie Newton was

their captain. They also had Bill Longley, he came to Hackney for

a few second half guest appearances. I liked watching him. He

stood just barely 5’0” and had to have a sandbag on his pillion

because he was so light. His bike would run away with him if he

didn’t have it on there to weigh it down a bit. |

| |

|

Me: You mentioned Georgie Newton. I believe

he was a very spectacular rider wasn’t he? |

| UA: Oh yes. He had very broad shoulders

and stooped over his handlebars, a bit like Jack Ormston. |

| |

|

| Courtesy of John Spoor |

| |

|

Me: What other first Division teams can you

remember? |

| UA: Well, our local derby was with West

Ham, which always brought out the crowds. Of course they had the

guv’nor of them all, Bluey Wilkinson. I think he was the best

rider I ever saw. Bluey means Ginger of course. But they also had

some other great riders, Arthur Atkinson, Tommy Croombs and Jimmy

Gibb. They were a lovely team. They also had Malcolm Craven, who

seemed to get better and better and went on to captain England. |

| |

|

Me: What else can you remember about your

visits to Hackney Wick? |

| UA: They used to put on some great

interval entertainment. I can remember a boxing match there once

between Jimmy Bitmead and Max Joachim. It was only one round of

three minutes but it was a cracking fight. |

| |

|

Me: Thank you. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| Stan Stevens |

| |

| By Norman Jacobs |

| |

|

| |

|

Norman says: One of my favourite riders of

all time is Stan Stevens. Never a star (except on that

never-to-be-forgotten night when he beat Barry Briggs at West

Ham!), but always a whole-hearted trier who gave his absolute best

every time and whose points were often the difference between

winning and losing for whatever team he was riding for at the

time. At West Ham he struck up a brilliant relationship with

skipper, Ken McKinlay, and their partnership would often result in

5-1s over the visiting team.

Some years ago, I interviewed Stan about his

life in speedway.

|

| |

Me: When did you first get interested in

speedway?

Stan: I went along to West Ham’s last meeting

of the 1946 season when I was about 12. It was absolutely packed.

I couldn’t get a programme, they’d sold out. But I was bitten by

the bug. I then went into cycle speedway and got quite good at

that, riding for England with Dave Hemus and Clive Hitch.

|

| |

Me: When did you progress to the real thing?

Stan: I started at California. I can’t

remember which year, but it must have been mid to late 1950s. Alan

Smith was a great help to me. He gave me good advice on which bike

to buy and how to look after it.

|

| |

|

Me: I believe you moved on to Rye House.

Stan: Yes, I went there in 1958, this was

just after Dickie Case sold it to the dog man [Les Lawrence], who

was only interested in running greyhound racing and scrapped the

speedway altogether. But Mike Broadbank came to an arrangement

with him to build a new track on what is now the go-kart track.

When the dog man saw the size of the crowds he agreed to move the

speedway track back to its original location. I also rode in a few

second half events when New Cross was revived by Johnnie Hoskins

in 1959.

|

| |

Me: Can you remember anything about New

Cross?

Stan: I can remember one meeting in 1961, it

was a World Championship qualifying round. I went into the pits

and saw Split Waterman in there cutting stripes in his tyres with

a knife. I said to him, “Why are you doing that? Does it help?” He

let out his famous laugh – you could always tell when Split was

racing as you could always hear this laugh in the pits -

and replied, “No, it

doesn’t do a blind bit of good, but it makes me feel better!” When

we met during the meeting itself, I outgated Split, but he flew

past me down the back straight. As he did so, he turned to me and

gave me a big grin. Of course, we didn’t wear masks in those days.

|

| |

Me: You actually rode for New Cross in 1963

didn’t you?

Stan: Yes, Wally Mawdsley and Pete Lansdale

took over New Cross in 1963 and entered them in the Provincial

League and they signed me up. Of course, as we know, they packed

up mid season. I won the very last race ever held there – the

Scratch Race Final. The crowds were very thin, so it wasn’t a

surprise when they announced its closure.

|

| |

Me: You went on to ride for West Ham when

they returned to league racing in 1964. How did that come about?

Stan: Well, West Ham closed in 1955 because

Jack Young decided not to return from Australia. The crowds were

dropping and they felt they couldn’t continue without their star

rider. It wasn’t just West Ham, crowds were falling everywhere,

even at Wembley. There was no atmosphere any more and you could

hear the echo of the bikes all round the empty stands. In 1964,

Sanderson still held the West Ham licence. He and Charles

Ochiltree now owned and promoted Leicester and Coventry and they

decided to revive West Ham. They signed up Bjorn Knutson and Reg

Luckhurst from Southampton as well as Norman Hunter and Malcolm

Simmons from Hackney. I found out that West Ham was opening from

the Oxford promoter, because Ronnie Genz was asked to guest for

West Ham in their first match, a challenge match away at Norwich.

I contacted the West Ham management and asked if there was

a place for me. Luckily there was.

|

| |

Me: You developed a good relationship with

Ken McKInlay while you were at West Ham didn’t you?

Stan: Oh yes. Ken was a great team rider. He

always looked round for me on the first bend and then get behind

me to keep the others out. I’d say he was one of the best team

riders of all time. Others in that category were Ronnie Moore,

Eric Chitty, Aub Lawson and Norman Parker. Ronnie was probably the

best of the lot. He was a master team rider, his throttle control

was something amazing. Other top riders like, Vic Duggan, Jack

Young and Tommy Price were not team riders at all, they just

wanted to win at all costs.

|

| |

Me: You stayed on and off until West Ham

finally closed didn’t you?

Stan: Yes, I had a few good seasons there but

the crowds dropped again and at the end of the 1971 season, West

Ham again announced its closure, but there was a short reprieve.

Romford was also forced to close at the end of 1971 because of

problems caused to local residents by the noise, so they moved to

West Ham for 1972 under the name West Ham Bombers. By that time

though the stadium had already been sold to housing developers. It

was agreed they could continue with speedway for one more season,

but that only lasted for six weeks until, in May, they were told

they had to leave. As it happened, no development took place till

October, so they could have stayed and got through the season. The

team moved off to Barrow.

|

| |

Me: You mentioned just now that West Ham

closed in 1955 because Jack Young didn’t come back. Why was that?

Stan: Youngie retired because he said he

wanted to see his family grow up and decided to stay in Australia.

As you know at that time, he was one of the top riders around, if

not the top rider, so

West Ham felt there was no chance of getting a suitable

replacement. With crowds already falling, they felt that crowds

would drop even further if they couldn’t track a star name of his

ability so they closed down. The funny thing about Young was that

although he was arguably the best rider in the world in the early

1950s, he couldn’t gate for toffees. He was often last out the

traps but by the time he entered the back straight he would be in

the lead, he used to pass the other three riders round the first

and second bends. He once said to Tommy Price, “I wish I could

trap.” To which Price replied, “Well thank Christ you can’t, or we

might as well all pack up!”

|

| |

Me: What is your most outstanding memory of

your time in speedway?

Stan: Funnily enough, it is a race I lost! It

was away against Edinburgh in the Provincial League in 1961. I

rode for Rayleigh. We were one of the favourites for the title

that year as we had a strong heat leader trio of Reg Reeves, Harry

Edwards and me, so we were expected to beat Edinburgh. But with

one heat to go, the scores were level and I was out in the last

heat with the unbeaten Reg Reeves, against George Hunter and Doug

Templeton. George very soon got the better of Reg, but we were

both comfortably ahead of Doug and it looked for all the world as

though it would be a 3-3 and a draw. But I can still vividly

recall what happened then. As I rode into the fourth bend on the

last lap, I could see the whole crowd in the main stand rise to

their feet as one and it was then that I realised that Doug had

got me. He had made an amazing manoeuvre to cut through on the

inside of me. Although I came last and in effect lost the match

for my team, I will never forget the sight of that crowd rising as

one to cheer their own rider home.

|

Me: Thank you, Stan. |

| |

|

| |

| |

| Mike Broadbank |

| |

|

By Norman Jacobs

|

| |

|

| Courtesy of J Spoor |

| |

|

Interview with Mike Broadbank Part One |

| |

|

Some years ago, when I was writing my History

of Rye House, I went to see Mike Broadbank to ask him about his

time at Rye House in the 1950s and 60s. He and his wife made me

very welcome and supplied me with refreshments throughout the day.

|

|

This first part is what Mike told me about

the 1950s…: |

| |

|

“I got into speedway through cycle speedway

after watching the real thing at Rye House as a nine year old. I

rode for Hoddesdon Kangaroos. I continued going to watch speedway

and, as I got older, I got to know all the riders and began

helping out in the pits, helping to push them off and other odd

jobs. |

| |

|

When I left school in 1949, Dick Case, the

promoter at the time, asked me if I would like a job at the track,

so I started work there for £3 10s a week. I helped him prepare