|

|

|

| |

| |

John Hyam

Part 4 |

| |

| |

| Hedon Stadium nr.

Hull The Dave Collins Saga

"Noisy" Jim Chalkley

Igor Baranov

Ron Johnson |

| High Beech, Epping

Forest, Essex Jack Ormston Canadian

Capers Byrd McKinney

Midget Cars v Speedway |

| |

| |

The

Mystery Of

Ron

Johnson’s

Two

Deaths! |

| |

.jpg) |

| |

| Ron Johnson as a Crystal Palace rider in

the early 1930s. |

| |

|

By John Hyam |

| |

|

A SIMPLE obituary message sent a ripple of excitement through

the speedway world.

It read: “It is regret that I have to inform you of the death

of Ron Johnson, pioneer of British speedway and ex-New Cross

team member.”

|

|

| Then came a line that was to lead to an

international investigation which eventually involved a judge of

the Supreme Court of Western Australia. It said: "Ron passed

away peacefully at his home in Bangor, North Wales, on Sunday,

January 15th 2006 aged 94 years." |

| |

|

Yet it had been well chronicled in various speedway publications

that Ron Johnson, then confined to a wheelchair, had died at his

home in Perth, West Australia, aged 75 years on February 4, 1983.

And there was further evidence that he had been buried in

Karrakatta cemetery on the outskirts of

Perth.

However, there were puzzling parallels between the ‘Ron Johnsons.’

Both had been married to a woman named Ruby! |

| |

|

The known speedway Ron Johnson’s short-lived marriage was in 1949.

The second Ron Johnson left a widow, who he had married in 1963. |

| |

|

Mike Russell, a family friend of the newly-emergent Ron Johnson,

said that he had know him for about 18 months. He said, “Ron told

me that he had been born in Australia and that his father’s name

was Charles. He had raced for New Cross. In that time, a report

circulated that he had been killed. The shock was enough to bring

on the premature death of both his parents, although before they

died they did find out the report was wrong. |

| |

|

“Ron never talked about his speedway career and would talk down

references to it. He also claimed that besides being a speedway

rider, he had been a stunt motorcycle rider in a ‘Globe of Death’

act.” |

| |

|

Johnson also told Mike

Russell that he had been a double for Dirk Bogarde in the

speedway film “Once A Jolly Swagman” and to have served in

submarines during World War Two.”

He also told Russell that

at one time he had been a start marshal at the motor racing

circuit at Silverstone and been awarded a plaque for his work

there. But Mike Russell added, “I never saw this nor any

mementos of his speedway days.”

|

| |

|

Johnson’s step-daughter Hazel Evans said Johnson was born in Coss

Cove, Australia. His mother was an opera singer while his father

had been an engineer. An extensive investigation in West

Australia involving the Supreme Court judge and speedway historian

Geoffrey Miller, Kwinana Beach track promoter Con Migro and

historian Ken Brown convinced me that the man who died in Wales

was not the speedway rider. |

| |

|

I have

also studied photos of the second Ron Johnson which were taken in

1963. He bears no resemblance to the Ron Johnson I knew in the

late 1950s and early 1960s who was born at Milton Douglas,

Duntocher, in Scotland on February 24, 1907.

His

parents emigrated to West Australia and it was there in the early

1920s that he started his speedway racing career in West

Australia. |

| |

|

In Britain, Johnson’s most successful years were pre-World War

Two and in the early post-war years, as a member of the

Crystal Palace and New Cross teams. He was also a leading

member of the Australian test team.

His career as a leading rider ended when he suffered a head

injury at Wimbledon in 1949. Johnson made several unsuccessful

come-back attempts, and retired in 1960. In the late 1970s,

Johnson was badly injured in a car accident in Australia and

spent the last years of his life confined to a wheelchair.

|

| |

|

Judge Geoffrey Miller said, “There are existing photos of Ron

Johnson in a wheelchair meeting various riders. He still had

the same features of those shown in the earlier days when he

was a speedway rider.”

The judge added, “Certainly Ron Johnson died in Western

Australia because Western Australians had to put together the

money to bring him back from England after his dismal failure

in attempting to return to the speedway track in the 1960s or

thereabouts.

|

| |

| “He was broke and had no money to ever go

back again. I cannot see that he could possibly have ended up in

Wales.” |

| |

|

The historian Ken Brown added, “I am 99 percent the man buried

in Australia is the speedway Ron Johnson.”

There was just one other intriguing coincidence - both Ron

Johnsons had a wife named Ruby. The speedway rider was briefly

married in 1949.

|

| |

|

Judge Miller said, “When I was writing a history of the WA

solo champions I spoke with his grand-daughter and she

questioned whether he had ever divorced her grand-mother.”

Johnson and Ruby Green parted in the early 1950s.

And, finally from West Australia, promoter Con Migro provided

a copy of the known speedway rider’s death certificate which

authenticated the place and date of his birth.

But there remains a mystery - why did another Australian named

Ron Johnson convince people for more than 40 years until his

death in Wales that he was the famous Australian rider?

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

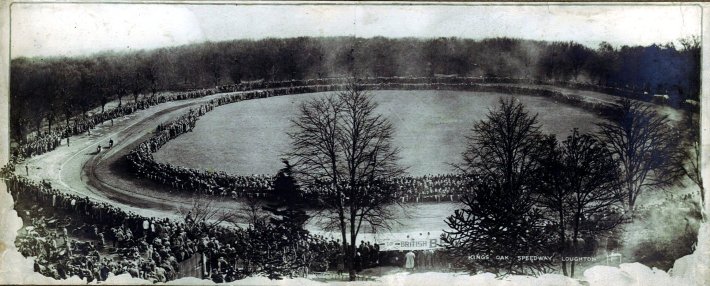

| High Beech |

| |

|

| Courtesy of John Spoor |

| |

| |

High Beech

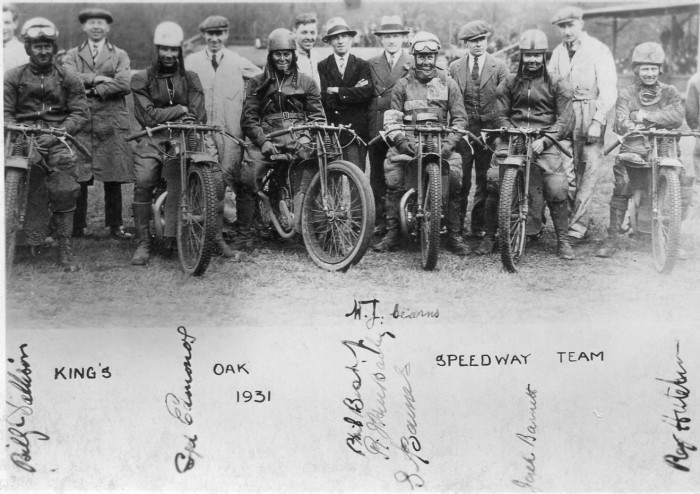

1931 Team |

| |

|

| Courtesy of Mike Kemp |

| |

| The 1931 High Beech team. The riders are - Billy Dallison, Syd

Edmonds, Phil Bishop, Stan Baines, Jack Barnett, Reg Hutchings

(Mike Kemp collection). |

| |

| |

Phil Bishop

In Action |

| |

|

|

Courtesy of the Mike Kemp Collection

|

| |

|

The darling of the High Beech fans - Phil Bishop in typical

legtrail action

|

| |

| This year (2015), speedway celebrates the 87th anniversary of what is recognised as the first British speedway meeting in February 1928

at High Beech. After a spell in early league racing, it became a

junior track in the 1930s, but eventually closed in late 1949.

JOHN HYAM writes of an hitherto unrecorded bid to reopen the

birthplace of British speedway in 1954. |

| |

| IT was one of the best kept secrets of 1954. An ambitious bid by

Doug Falby, then editor-owner of the 'Speedway Gazette', to reopen

the birthplace of speedway at High Beech as members of the

Southern Area League. |

| |

|

Since its original opening in February, 1928, High Beech had been

strongly associated with the sport. Sometimes known as King's Oak,

the track had competed in the old Southern League until the early

1930s. |

| |

|

Even after the venue dropped out of league racing, it still

featured as a junior track at various periods up to the start of

World War Two in September 1939. And, apart from

its motorcycle speedway associations, in 1937 and 1938 High Beech

had also staged meetings for midget cars which were then trying to

make their mark as an alternative speedway sport. |

| |

| Post-war, High Beech returned to

action in 1948 and 1949 with a series of open meetings - running

very much as an alternative junior track to Dickie Case's vibrant venture at nearby Rye House. |

| |

|

Among the post-war riders at High Beech was Allen Briggs - later

to be associated with Walthamstow and Rayleigh. Another was Steve

Bole, who had a brilliant one season with Eastbourne in their SAL

days, then surprisingly quit racing at the end of 1954. |

| |

| And a great stalwart and favourite at High Beech in the years

spanning World War Two was Arthur Sweby, a rider who also made a

name for himself on southern grass tracks. |

| |

| While these riders never matched the calibre of the original High

Beech aces of the 1920s and 1930s like Phil Bishop, Jack Barnett,

Syd Edmonds and Stan Baines, they nevertheless were an integral

part of the Essex track's history. |

| |

| And legend has it that in the only

recorded match race between a male and female rider which took

place at High Beech in 1929, South African favourite Keith Harvey was run into by an unnamed

woman rider. She escaped injury, but Harvey suffered a broken leg. |

| |

| This, however, gets away from the attempt

to revive High Beech for entry to the SAL in the mid-1950s. Falby, of course, was well

placed to act as a speedway promoter. In pre-war years he had been

business manager to former rider Arthur 'Westy' Westwood. In his

time, Westwood promoted in France - at the Buffalo Stadium in

Paris and at Marseille. And just before war broke out, he had been

involved as promoter of the Birmingham, Nottingham and Leeds teams

in the old National League's Second Division. Post-war, Westwood

ran at Tamworth in 1947 and 1948. |

| |

| Falby was convinced that High Beech would be a welcome addition to

the Southern Area League, which in its initial 1954 season

featured Aldershot, California (Wokingham), Eastbourne, Brafield,

Rye House and Eastbourne. |

| |

| The moves towards a High Beech revival

started in the mid-summer of 1954 when Falby enlisted me to help him draw up the framework

for the venture. The first thing was to form the basis of the

team. |

| |

| High on the list was the former

Southampton and Liverpool legtrailer George Bason. He had started the 1954 season with

California, then dropped out of the side after six weeks to

concentrate on his business. But he still turned out in open

meetings at California. I assured Falby he could be persuaded into

racing for High Beech. |

| |

|

It was also planned to target another of the California regime,

Ted Pankhurst, who had raced briefly for the 'Poppies' at the

start of 1954 before reverting to his first track love grass track

racing and a career in the then new British track sport stock car

racing. |

| |

| Also on the High Beech hit-list was the

former Oxford junior Ray Terry, who was then breaking into an

injury-hit Eastbourne team. And colourful spectacular Johnnie 'Cisco Kid' Fry - another

Eastbourne rider - was also on Falby's team sheet. Veteran

grass trackman Tom Albery - famed for his brown racing leathers -

who had also raced a few times on speedway for California was

another ‘wanted man.’ |

| |

| Stan Tebby, the grass track racing father of Jim Tebby (later a

long-time loyal servant to Wimbledon) was pencilled in, as were

juniors John Lalley, Al Holliday (briefly with Rayleigh in the

early 1960s), cousins Keith and Ronnie Webb, Irish junior Mike

O’Connor, and an Australian youngster John Gronow. |

| |

| Gronow had first arrived in England in 1953 primarily to race in

the Isle of Man TT. But on the ship to England he came into

contact with English rider Maury McDermott (Harringay and

Rayleigh). Gronow liked what he heard about speedway and decided

to switch racing formulas. |

| |

| Lalley, from Camden Town in North London, was a protege of the old

West Ham, Norwich and Aldershot favourite Ivor ‘Aussie’ Powell.

Lalley also pinned his faith in what was, for that time, a

revolution in bike engine positioning. It was placed on a slope in

the frame - the forerunner perhaps of the modern laid-down engine.

Powell achieved much success with the bike - sadly Lalley never

emulated his mentor. |

| |

| With that part of the equation finished,

at least on paper, the next objective was an inspection of the

High Beech facilities. That's where I again came in. I was then

regarded as an 'expert' on the SAL and its track requirements. I

was writing regular columns on the SAL for the 'Gazette',

'Speedway Star' and 'Speedway News'. Falby said: "You know what the league's all

about. Go and take a look at High Beech for me." |

| |

| I did not own a car at the time, but I had

a rather fine drop-handlebars racing-type cycle. More importantly,

I was also keen on the chance of becoming a promoter in the mould of

Johnnie Hoskins, so I agreed to inspect High Beech. |

| |

| It involved me in a 30-mile round cycle

journey from my south London home to High Beech on the far north

east outskirts of the capital. I vaguely knew where the track was,

and after biking through the East End, eventually went through Ilford and Romford,

before finding Epping Forest and High Beech. |

| |

|

I was horrified when I saw the birthplace of speedway. The safety

fence had long since gone, what had once been a stand of sorts was

derelict, it was difficult to find the pits area, and the

race circuit was overgrown. |

| |

| As for the centre green, this had become a storage area for beer

crates. I had never seen so many in one place - hundreds of them,

neatly stacked and placed there for storage by the brewery

which looked after the interests of customers at the nearby King’s

Oak pub. |

| |

|

| |

| Despite my enthusiasm, even I knew that a

speedway revival at High Beech was a non-starter. For the type of

Sunday afternoon racing supplied by the SAL and the low

attendances the league attracted, only a fool would have poured

cash into a venture that would never recoup a substantial cash

outlay. I reported my findings to Doug Falby and he agreed with me: High Beech would never see another

speedway meeting. And it never did. |

| |

| Luckily, Falby had curbed an initial wish by me to hint at a 'High

Beech speedway revival' story for the ‘Speedway Gazette’. We both

felt that as things stood it was best to keep quiet our

moves in that direction. |

| |

|

And that's how things have been for more than half a century. But

it's good to get things out into the open and I feel now is the

time to make public the sad tale of the last bid to promote at

British speedway’s pioneer venue. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

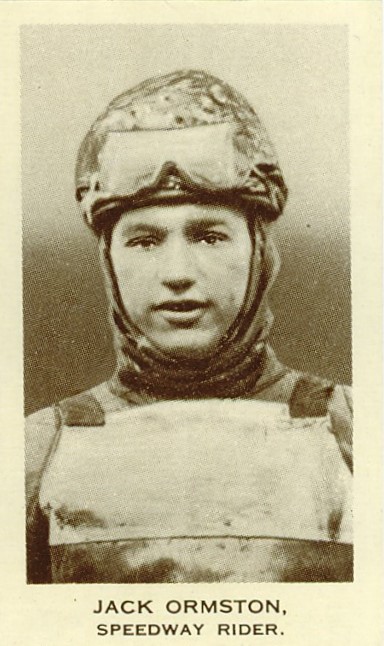

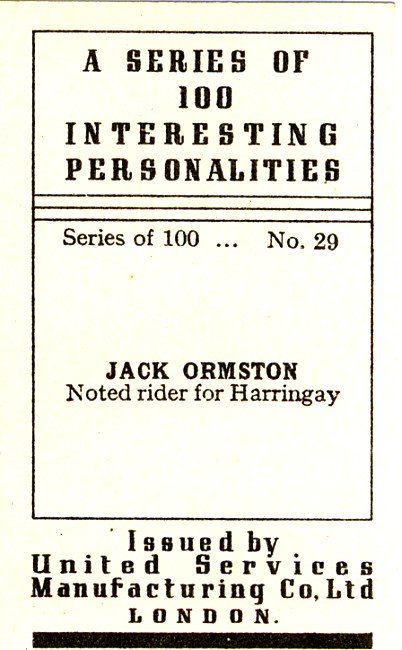

| Jack Ormston |

| |

|

| Courtesy of David Pipes |

| |

| by John Hyam |

| |

| When Jack Ormston died at his home on June

22, 2007, aged 97 years, it ended the last of the sport's links

with the 1928 pioneer days. Ormston was also the last surviving

starter from the first World Championship in 1936. |

| |

| John Glaholme Ormston was born in West

Cornforth, County Durham, on Saturday October 30, 1909. When he

was 14 years old, Ormston developed an interest in cars and

motorcycles. The passion often brought him reprimands from the

local police - especially when they caught him driving the

family's American Buick car. |

| |

| In 1926, 17 year old Ormston took up grass

track racing. It was good grounding for when speedway arrived in

Midlesbrough in 1928. Ormston's reputation reached the south and

he started to race at Wembley. |

| |

| When league racing began in 1929, Ormston

was an influential member of the Lions' squad. He won the first

London Riders Championship at Crystal Palace in 1930 and that

season was also selected for England in the first ever test match

against Australia who won 35-17 at Wimbledon on June 30. |

| |

| After touring Australia in 1932-33,

Ormston went to the USA as partner to Australian star Frank Arthur

in a bid to establish speedway at the Madison Square Gardens in

New York. They also recruited Johnnie Hoskins as their racing

manager. The venture collapsed when Ormston withdrew financial

support to return to England when his father died. |

| |

| Ormston sat out the 1933 campaign to

manage the family butchery business but returned in 1934 at

Birmingham (Hall Green), then joined Harringay in 1935 where he

stayed until his retirement at the end of the 1938 season. |

| |

|

| Courtesy of John Hyam |

| |

| Ormston was a prominent challenger in the

Star Championship, the foreunner of the World Championship. His

best performance was in 1935 as runner-up to Frank Charles, and

ahead of Max Grosskreutz. |

| |

| At the first World Championship at Wembley

in 1936, Ormston was joint fifth in a meeting won by Lionel Van

Praag. Ormston's other world final appearance was in 1938 when

Bluey Wilkinson took the crown. Ormston rode for England against

Australia in six domestic test series and went down-under with

England sides in 1936-37 and 1937-38. |

| |

| At the top of his career, Ormston earned

£15,000 a year and lived at the Park Lane Hotel. This was when

professional footballers earned a £6-a-week and the

man-in-the-street £190 a year. |

| |

| Ormston took up flying in 1929, using a

bright red Westland Widgeon monoplane which he kept in a shed near

his northern home. To the delight of local villagers, he gave

unauthorised displays of skimming the rooftops and

looping-the-loop. His best feat as a serious flier in the

mid-1930s was to finish second in the Grosvenor Cup. He also twice

finished in the King's Cup air race. |

| |

| In pre-war years, Ormston was a respected

amateur steeplechase jockey. He became a trainer in 1940 and had

400 winners to his credit when he retired in 1976. His most famous

horse was Le Garcon d'Or with a record 34 flat race wins. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

Igor Baranov |

| |

|

| |

|

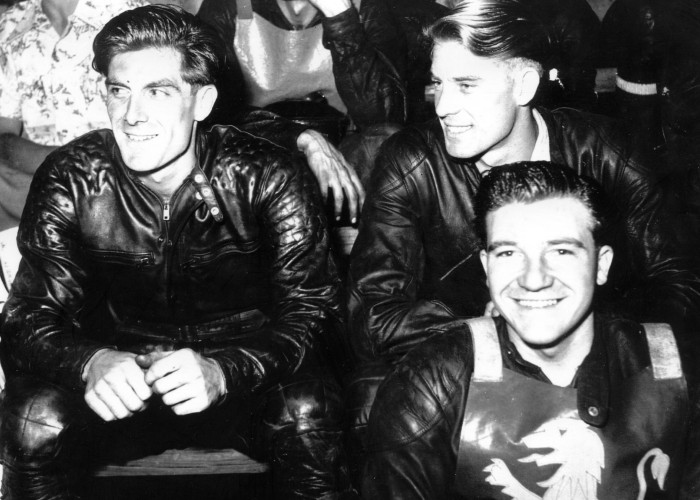

John Hyam says: The name of early 1960s Russian rider Igor Baranov

will mean little to most speedway followers. He turned up with

much local publicity for a second-half ride at New Cross in the

early 1960s. |

| |

|

Amidst a lot of ballyhoo by the then New Cross boss Johnnie

Hoskins, Baranov appeared on what looked to be a newly-chromed

bike and wearing a red race jacket complete with the

hammer-and-sickle emblem. |

| |

|

His arrival at New Cross came at a time when Russian fishing

fleets were alleged to be over fishing traditional British areas

in the North Sea. So, in his introduction, Johnnie told fans,

"Igor has escaped from the Red Herring fleet!" |

| |

|

In his race, Baranov was outclassed, but that didn't upset

Johnnie. He told supporters, "We have still to see the best of

him."

But that never happened, and those who bothered to check for

further details on the Russian found no evidence of him as a rider

in his claimed homeland. |

| |

|

Eventually, it leaked out. Igor Baranov was British junior Jack

Jones who had been persuaded to take part in another Hoskins'

publicity stunt. Those who knew Hoskins better should have spotted

the giveaway clue when Johnnie mentioned the words 'Red Herring.' |

| |

|

| |

| New Cross promoter Johnnie Hoskins

changed the nationality of British junior Jack Jones. |

| |

|

Jones was not seen again at New Cross, but he did have outings at

Stoke and Wolverhampton in the early days of the Provincial League

in the 1960s. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

| Part 1 |

| |

| JOHN HYAM begins an in-depth survey on the

influence of Canadian speedway riders on the sport in Britain in

the pre and immediate post-war years. |

| |

|

| Courtesy of J Spoor |

| |

|

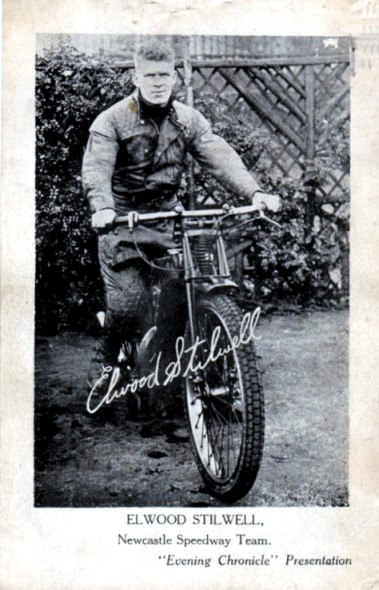

Col Greenwell says: The names I have for your

pre war Canadian team are...George Pepper,

Robert Spark, Kid Curtis, Bruce Vernier, Elwood

Stilwell. Interesting eh..!!..as all other old

mags etc say Kid is from London, which I would say is

correct. |

| |

| CANADA has always been very a much a

backwater of speedway racing, writes John Hyam. Only two riders -

both from the 1930s and 1940s - have achieved recognition at

international level. They were Eric Chitty, who made his mark with

West Ham, and Jimmy Gibb, who had two pre-war seasons alongside

Chitty at Custom House in 1938 and 1939. Post-war, Chitty

had several excellent seasons with the Hammers while Gibb came

back for the first time in 1949 when he rode for Wimbledon. He

stayed in the USA in 1950, but had another season with the Dons in

1951. |

| |

| |

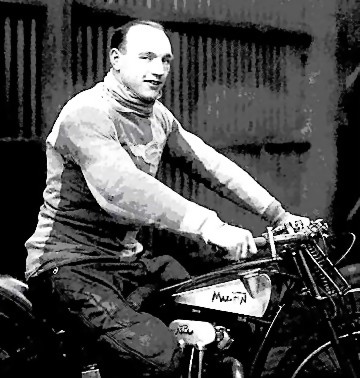

Newcastle's Best Canadian Import George Pepper

1938

& 1939 |

| |

|

| Courtesy of J Spoor |

| |

| There were

other Canadian riders who came to Britain in the immediate

pre-World War Two seasons. Undoubtedly the

best of these was George Pepper, who first turned up at

West Ham in 1938, but was posted by the First Division

club’s promoter Johnnie Hoskins to his newly formed Second

Division track at Newcastle. |

| |

|

In 1937, Pepper was on the verge of dropping out of

cross-Atlantic speedway to follow a career in road racing,

but was persuaded by Chitty and Gibb to try British

speedway racing. He actually arrived in Britain in 1938

with the purpose of riding in the Isle of Man TT.

|

| |

| Pepper was an immediate star at Newcastle and became

the track record holder, which stood well into the

post-war seasons. He developed into one of the Second

Division’s top riders and many experts predicted that he

was destined for the sport’s highest honours. Had war not

started in 1939, it is certain he would have joined Chitty

and Gibb at West Ham for the never held 1940 season. |

| |

| Jeff Lloyd, who was a post-war star at

Newcastle, New Cross and Harringay, had some vivid memories about

the hard racing style of Pepper. When racing for Middlesbrough

in 1939, Lloyd was going for a maximum against Newcastle

when he met Pepper who went on to beat him. Lloyd said of

Pepper’s tactics: “Considering my inexperience, Pepper was

far more aggressive than he need have been in beating me.”

But that was probably typical of Pepper - as it was of

Lloyd. Both wanted to be the best and rode to achieve

that. |

| |

| Pepper volunteered for war service

in September 1939 and after initial pilot training served with the

RAF’s 29 Squadron, firstly flying Blenheims, then the Bristol

Beaufighter. He distinguished himself by shooting down six

German aircraft and was awarded the DFC and Bar. Pepper

was 26 years old when he died in a flying accident on

November 17, 1942, and is buried in his home town

Belleville, Ontario, Canada. Eric Chitty recalled

the tragedy that befell his fellow countryman. He said: “One day

he took a plane up for a test flight. The engine cut out and

Pepper failed to get out before it crashed into the ground.” |

| |

| Pepper’s last meeting for Newcastle was on

August 28, 1939, when 10,862 fans saw them beat Sheffield 48-38.

He scored a maximum 12 points. The following Sunday, September 3,

war was declared and speedway virtually closed down in Britain. He

did, however, race in a handful of the 1940 war-time meetings at

Belle Vue. |

| |

| Chitty arrived at West Ham in 1935 to fulfil an

invitation made to him some years earlier by Hoskins who

had seen him racing on tracks in the USA’s Eastern States.

He struggled for some two years to make the grade, but

when he did show improvement, Hoskins decided he wanted

more Canadian riders. There were restrictions on

European and American riders getting contracts with British teams

but, as was the case with Australian, New Zealand and South

African riders - who were citizens of British Empire countries -

there were no restrictions on Canadians. |

| |

| Gibb made his mark in Britain from the

start, and was probably a shade ahead of Chitty in racing ability.

Besides his experience in the USA and Canada, Gibb had also

campaigned with Americans Jack and Cordy Milne in

Australia in the mid-1930s, When war broke out in late

1939, Gibb was the tenth highest scorer in the National

League’s Division One, although Chitty was only a few

places behind him in the charts. |

| |

| For their part, both riders were proving

themselves on a par with their Trans-Atlantic cousins from the USA

like Jack and Cordy Milne, Wilbur Lamoreaux and Benny Kaufman.

But while the Milnes and Lamoreaux made a major impact on

the World Championship scene in the immediate pre-war

years, Canada did not enjoy the same success. |

| |

| In 1937, Chitty was 16th with four

points and in 1939 was the 10th leading qualifier in a final

postponed because of the start of World War Two. Gibb went to the

1938 world final as a reserve but did not ride in the meeting In

the post-war British Riders Championship, which replaced the World

Championship between 1946-48, Chitty qualified for all three

finals. In 1946 he was seventh with nine points. The 1947

championship saw him move up to fourth place with 10 points, and

the following season he was 12th, scoring five points. |

| |

| Chitty had come to the forefront in 1938,

starting that season with a sensational win in the London Riders

Championship at New Cross. This was then a highly regarded event -

attracting the top riders from the host track as well as Wembley,

Wimbledon, Harringay and West Ham. Such was the wealth of talent

assembled for the LRC, it was generally regarded as a pointer

towards who might be crowned that season’s world champion.

With the outbreak of war, Chitty stayed on in Britain, and after

serving briefly as a War Reserve policeman, tried to enter the

Army. By then, he was also engaged on essential war work and his

bid to enter the forces was refused because of the work he was

doing. |

| |

| Although speedway to all intents and

purposes ground to halt for the war years between 1939-45, a few

meetings took place in early 1940 at Crystal Palace,

Southampton and Rye House. As a London-based rider, Chitty

appeared a couple of times at Rye House. In later war years,

he became a regular in the Saturday afternoon war-time meetings at

the old Belle Vue track at Hyde Road,

Manchester. It was in these meetings, racing

against topline stars including Jack Parker, Ron Johnson, Bill

Kitchen, Frank Varey, Eric Langton and Joe Abbott, that Chitty honed his

racing skills. Proof of this was his victories in a couple

of the unofficial British Riders’ Championships. And when

the war ended in 1945, Chitty was also a member of a NAAFI

team that went to Germany for a series of international

meetings to entertain British soldiers. He was very much

the star rider of the group. |

| |

| This sort of form made Chitty a ‘must’ for

the West Ham side when speedway resumed on a league basis in 1946.

Former Hammers’ rider Arthur Atkinson and his partner Stan Greatrex, the old New Cross favourite, who had taken over

the Custom House promotional reins from Hoskins, had no

hesitation in appointing Chitty as their team captain. |

| |

|

Gibb, however, was missing from the riders who returned to

Britain for the early post-war seasons. In the early

1930s, Gibb had flourished on a series of tracks centred

on New York State and had also been winner of both the

Canadian and USA Eastern States Championships. He

preferred the cut-and-thrust of individual racing, and

after the war resisted offers to come back to Britain.

By then, Gibb was also holding down a well paid job as

a film studio cameraman in Hollywood, and was combining

this work with racing at various tracks in California

against old rivals like the Milnes, Lamoreaux, Charles

‘Pee Wee’ Cullum, Manuel Trujillo, Bud Reda and Chuck

Basney.

|

| |

| It was something of a surprise when

Wimbledon promoter Ronnie Greene enticed Gibb to Plough Lane just

after the start of the 1949 season. He immediately added

much-needed punch to a flagging Dons team and showed all the

brilliance associated with him by British fans some 10 years

earlier. |

| |

|

But the late 1940s and early 1950s were a time of economic

depression. When the pound sterling was devalued against

the US dollar just before the opening of the 1950 season,

Gibb decided it was not financially viable to make another

racing trip to Britain. But he was back for one more try

in 1951 at Wimbledon and also raced in Sunday meetings at Shelbourne Park (Dublin). And, to add debate

about his nationality credentials, some claimed he was

really an American, he also rode for the touring USA team

in their test series against the England ‘C’ squad.

(To be continued).

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

Canadian Capers

Part 2

By John Hyam |

| |

|

| Courtesy of J Spoor |

| |

| The 1938 Canadian team. Front - George

Pepper, Johnnie Hoskins (promoter) , Eric Chitty and daughter

Carol Anne, Jimmy Gibb. Back - Goldie Restall, Eddie Barker, Bob

Sparks, Elwood Stilwell, Bruce Venier. |

| |

| |

| ERIC Chitty, Jimmy Gibb and George Pepper

are the Canadians recognised as having made most influence on the

British scene in the years either side of World War Two. In the

conclusion of his analysis, JOHN HYAM records the efforts of

lesser known Canadian riders. |

| |

|

THE pre-war years brought other Canadians besides Eric Chitty,

Jimmy Gibb and George Pepper into British racing.

One of them was Harold Blain, who fleetingly flitted across

the Birmingham scene in 1937, while Johnny Millett was

another Canuck who came to Britain but failed to get a team

place after trials at New Cross and Birmingham. In 1939, then

West Ham promoter Johnnie Hoskins intimated he was prepared to

give Blain a second chance in Britain, but the deal never

materialised.

|

| |

| Blain and Millet had been early 1930s

starters with Chitty, Gibb and Pepper at the Ulster Stadium track

in Toronto, Canada, and on the USA’s Eastern seaboard. For around

five years, they were accompanied on this racing schedule by

Goldie Restall, Crocky Rawding, Bob Sparks, Elwood Stillwell and

Bruce Venier, These riders also turned up in Britain in the last

two pre-war seasons. Sparks, Stillwell and Venier lined up with

Pepper at Newcastle in 1938, while Rawding and Restall were

associated with New Cross. |

| |

| Another Canadian was Eddie ‘Flash’ Barker,

a former all-in-wrestler, who rode at West Ham in 1938 and 1939.

Barker also went for a race-winning trial at Crystal Palace in

June 1939, only for the track to close after the meeting because

of lack of support. |

| |

| At the time, another Canadian Charlie

Appleby was just holding down a reserve berth at the Palace.

Appleby, who served in the RCAF during the war, died from injuries

on October 8, 1946, while a member of the Birmingham team. He was

seriously injured in the previous night’s meeting at Newcastle

when he crashed when avoiding a rider who had fallen in front of

him and died from his injuries. Appleby had originally turned up

in Britain at Hackney in 1938 and following the Palace’s closure

in mid-season 1939 returned to Waterden Road. During the war,

Appleby flew on 150 missions as an air gunner with Bomber Command. |

| |

| Barker came back to Britain after the war

in 1947 and resumed his wrestling career with some success. In his

speedway days at West Ham, Barker was a great favourite with

Johnnie Hoskins. When the ‘great man’ first signed the 14-stone

Barker he said: “When he’s around the Hammers side, we know

there’ll be no physical problems from the other team.” |

| |

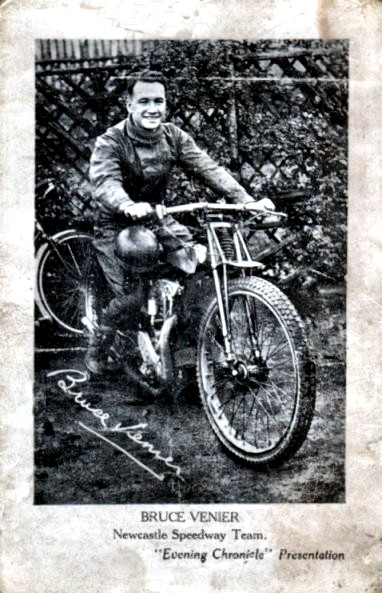

| Bruce Venier spent the 1938 season with

Newcastle, in a race term where he also competed at the Marine

Gardens in Edinburgh. Pepper and Stillwell came back for 1939,

with Pepper racing regularly at Newcastle, Marine Gardens and

White City Glasgow. Stillwell was out of favour at Newcastle in

1939 but raced 10 meetings at Glasgow and in three meetings at

Marine Gardens. Another Canadian who turned up at the Scottish

tracks in 1939 was Fred Belliveau, a 24-year-old who originally

signed for Wembley. They loaned him on to Middlesbrough and when

that track closed in mid-season he moved on for trials with Stoke,

who also dropped out of the league. |

| |

| Restall and Rawding both had misgivings

about racing in England. When Restall arrived at the start of 1938

he said: “It will be difficult to adapt. Tracks on the USA East

Coast are mainly clay rather than cinder surfaced, while many

races are rolling rather than clutch starts.” |

| |

| The reason was that on the East Coast USA

and in Canada, at many venues speedway was only an additional

class to motor-cycle flat-track racing and races were run largely

according to the rules of the latter formula. Most of the

Canadians tended to race at these venues, whereas Gibb and Chitty

had done much of their racing at purpose-built American speedway

tracks and consequently adapted more easily to British racing

conditions. |

| |

|

By August 1938, Restall was down to second-half rides at New

Cross and made an unsuccessful bid to go on loan to Second

Division side Bristol. At the end of the season, he was not

retained by New Cross, but appealed for another try with the

club for 1939 and was brought back. He showed marked

improvement and had scored 54 points when the sport ground to

a halt because of the outbreak of war on September 3.

New Cross, also signed Rawding for the 1939 season. He

originally came to England with Belliveau to ride for Wembley.

There was a row between the two clubs before Rawding opted for

New Cross. Like Restall, he was disappointed with his form in

Britain, and found British track conditions hard to adapt to.

His reputation had been built on tracks around New York.

|

| |

| In 1935, Rawding was runner-up to Gibb in

the USA Eastern States Championship, was second to Benny Kaufman

in 1936, then in 1937 and 1938 was beaten by former Wimbledon

rider Bo Lisman. In his first match for New Cross, Rawding

crashed and broke his collar-bone. When he recovered he moved

across south London and was a reserve rider for Wimbledon and up

to September had scored 17 points. |

| |

| Venier was a surprise starter for British

racing in 1947, when Ian Hoskins signed him for Glasgow White

City. The Canadian made his debut on April 9 in a challenge match

against the Oliver Hart Select, and the following week turned out

in a league match against Norwich. He fell in all his races in

both matches, although in one meeting he was twice in the lead

when he crashed. In both matches, the Canadian was riding the

White City track spare and using borrowed leathers. In Venier’s

last match, Hoskins recalls that when he crashed he tore the seat

out of his borrowed leathers and vanished to the dressing rooms.

He added, “I was surprised when Venier presented himself at White

City. He had no equipment, just a reputation gained at Newcastle

before the war. On that, I gave him a chance.” |

| The next day after his last rides at White

City, Venier turned up at the stadium and persuaded Hoskins to

lend him £10 for the fare to London, from where he planned to

return to Canada. Hoskins never heard from him again, but years

later told me: “I was in Toronto in 1980 and heard that Venier was

driving taxis. I never found him, so I’m still owed a tenner.” |

| |

| Two other Canadians who turned up in

Britain immediately after the war were Bill Matthews and Mike

Tams. It was Eric Chitty who persuaded Matthews, a top performer

on one-mile and half-mile dirt tracks in Canada and the USA, to

try speedway at West Ham in 1947. But try as he did, despite a

mid-season loan spell to gain experience at Second Division

Birmingham, Matthews never made the transition to speedway.

Matthews was winner of the annual 100-mile dirt track race at

Daytona in 1941, and repeated the feat in 1949. Because of these

achievements he is recognised as being one of Canada’s top riders

in this form of track racing and has a place in American

motorcycling’s ‘Hall of Fame.’ Mike Tams, who had arrived in

Britain pre-war with his family as an 11-year-old, decided on a

speedway career in 1946 and was a member of that winter’s

Harringay training school at Rye House. He linked with Third

Division Eastbourne for 1947 where he mainly rode in second-half

races. |

| |

| Wembley made an inquiry to buy Tams but

their team boss Alec Jackson baulked at the Eagles’ £500

valuation. In 1948 and 1949, Tams was rider-promoter at Santry in

Ireland, then in 1951 rode for Newcastle in the Second Division,

before spending a couple of seasons with Southampton. In 1955,

Tams turned out for Ringwood in the Southern Area League, and was

at one-time holder of the section’s match race championship. |

| |

| His stay in the SAL was brief - the

Control Board banned him from the competition on the grounds he

was ‘too experienced.’ Disillusioned, he returned to Canada. In

1960, Newcastle promoter Mike Parker signed him to lead the

‘Diamonds’ in the newly-formed Provincial League. At the last

minute, Tams dropped out of the deal, staying in Canada to promote

speedway at Dundas and then Welland with former Stoke, Motherwell

and Liverpool rider, Englishman Stan Bradbury. |

| |

| Mike Tams’ younger brother Les also had a

spell with him at Eastbourne in 1947, but declined the chance to

move to Hastings the following season when the Eagles’ moved

there. In 1948, Les and Mike were involved in a bid by then Belle

Vue rider Wally Lloyd to promote at Belfast in Northern Ireland

before linking with Santry in the Irish Republic. |

| |

|

It was then that Les became known as Les Gordon. Mike

explained, “It was felt that one Tams around a place was

enough for most people!” On August 29, 1948, Les scored two

points for Ireland who lost 39-33 to England at Santry.

Mike added, “Early in 1949, Les gave up racing. He went to

work for Ford at Dagenham, then reverted to his trade of

plumber and for many years was involved on housing

developments in the south of England.”

|

| |

| |

| Mike Tams |

| |

|

| Courtesy of J Spoor |

| |

| Mike Tams Canada. Newcastle 1950-51 Southampton 1952-53. |

| |

| Eric Chitty, Jimmy Gibb and George Pepper

were the leaders of the pre-World War Two invasion of British

speedway by Canadians. In the 1960s, Dave Dodd rode for Poole and

Liverpool. After his spell in British speedway, Dodd raced a

couple of meetings at Welland before contracting cancer, from

which he died. |

| |

| |

More Canadians In Newcastle's

1938/39 Teams |

| |

|

| Courtesy of J Spoor |

| |

| Newcastle's Canadians, 3rd from Left Bruce

Venier. 5th Elwood Stillwell and 6th Bob Sparks. George

Pepper was also a member of the 1938 and 1939 Diamonds teams but

he is not in this photo. |

| |

| |

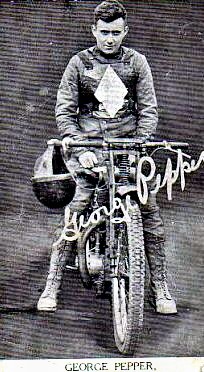

| George Pepper |

| |

|

| |

| |

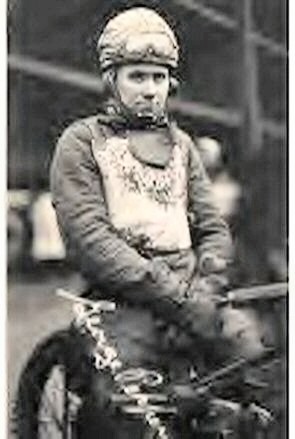

| Bruce Venier |

| |

|

| Photo's courtesy of John Hyam and J Spoor |

| |

| |

| Bob Sparks |

| |

|

| Courtesy of J Spoor |

| |

| |

| Elwood Stilwell |

| |

|

| Courtesy of J Spoor |

| |

| John says: My thanks to John Hyam for this

very interesting article entitled Canadian Capers and a thank you

to J Spoor for supplying some of the pictures. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

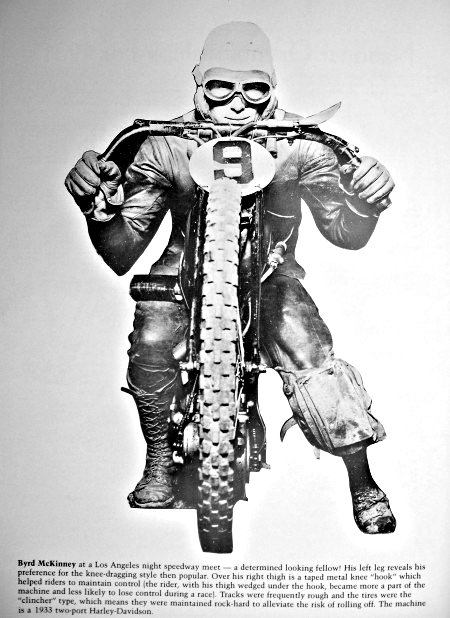

1933 Photo of Byrd on a 1933 Harley Davidson. Courtesy of J Spoor |

| |

| AMERICAN rider Byrd McKinney had a brief

spell with Wimbledon in 1937. Writes John Hyam. I believe he

also raced in the UK in 1936 as a member of Putt Mossman’s teams.

In Britain, |

| |

|

| |

| McKinney does not rate alongside his more

famous fellow countrymen, but it seems he built a good reputation

in the USA. Here is some information passed on by an American

contact: |

| |

| McKinney was third at the very first USA

National Championship in 1934 for what they then called night

speedway. For some reason what we call speedway today was spun off

by itself or at least was identified as a special form of dirt

track racing. This was probably due to what was happening in the

rest of the world. |

| |

| Class "C" (or flat-track) didn't exist in

the early days and only spotty in the run up to WW2. After the war

it took over and Class "A" which once was everything, sidecars

included, all but died. |

| |

| In 1934, the USA Nats were held at the

Los Angeles Coliseum and McKinney came third behind winner Cordy

Milne and Lammy Lamoreaux. He was third again the next year at

Fresno State College Speedway. Cordy Milne won it and brother Jack

tied with Miny Waln for second, McKinney tied with Pete Coleman

for third. I don't have any run-off info so presume these were the

final results. |

| |

|

“McKinney also won the 100 mile Ascot race in 1934. Speedway

bikes ran longer races with bigger tanks, mounted the usual

way like a regular bike, on top of the diamond.”

When speedway revived after WW2 in California, McKinney came

back for several seasons and was again a leading rider in

California.

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

John Hyam writes: It took a lot to upset renowned cricket

commentator John Arlott, but a speedway rider managed to do it in

1952! |

| |

|

| |

| Jim Chalkley, then with Rye House, in

action at Rayleigh in 1956 and the BBC's Cricket Comentator John

Arlott |

| |

| |

|

The incident happened when then Southampton rider, the late Jim

Chalkley, was working on his bike in the pits. He said, "I

decided to tune the carburetor, so I started the engine and kept

revving it up for it to be warm enough for me to do some

adjustments. |

| |

|

"Suddenly I realised there was a man looking over the fence at the

back of the pits. He was really angry and shouted turn that bloody

bike off we are trying to do a commentary on a cricket match for

the BBC'. |

| |

|

"What I didn't know was that the Hampshire cricket ground was

neighbours to Southampton speedway."

Chalkley added, "Later I heard references to the incident on

the BBC radio's 'Programme Bloopers.' It features John

Arlott's commentary from that day. "He

actually says 'some idiot's revving a motor bike the other

side of the fence while I'm trying to do a commentary.' John

was correct because you can clearly hear my bike's engine in

the background."

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| Dave Collins |

| |

| Part One

By John Hyam |

| |

|

As a schoolboy, Dave Collins used to sneak in at pre-war

West Ham meetings. After World War Two service in the Royal Navy,

he emigrated to South Africa to work as a gold-miner and earned

enough money to buy a speedway bike. |

| |

| When Dave Collins left his London home in

late 1947 for South Africa it was to find fame and fortune as a

gold miner.

Collins never found that elusive pot of gold, but he did find fame

as a speedway rider and for some 20 years was a well-known figure

in the sport in the Republic. |

| |

| Collins, born in 1926, is now in 2015, 88 years old and living in Munster, South

Africa, he recalls: “Before the war, I was a keen West Ham

supporter and from around 1937 used to sneak myself into the

Custom House Stadium without paying. That was naughty of me, but

that sort of thing was a way of life then for East End kids.” |

| |

|

The 1938 world champion ‘Bluey’ Wilkinson was Dave’s big

hero, although there were other pre-war West Ham stars he admired

including the Canadians Eric Chitty and Jimmy Gibb, and the

England ace Arthur Atkinson. |

| |

|

Collins was born in Plaistow in London’s East End, and in the

closing years of World War Two saw service in the Royal Navy.

“When I came out of the forces in 1947, I tried to get into

speedway racing but just could not afford it. I was wondering what

to do with my life when I saw an advert in an evening newspaper

for gold miners to work in South Africa. |

| |

|

“In March 1948, I started an eight-month stint working underground

at 10,000 feet - that’s nearly two-miles. It was dreadful - no

place for human beings really, but I needed the money. When I left

the mines, it was just as a boom for speedway was starting and I

bought a bike on hire-purchase terms from Buddy Fuller, who was

promoting and riding in South African meetings. |

| |

|

“My first competitive meeting at Dunswart in 1949 proved a

disaster. In my first ride I hit the safety fence and broke my

collar-bone. But I persevered and established myself in South

African speedway. Before leaving for England at the start of the

1951 British season, I sold my bike to another rider who promised

to forward the money to me in England. |

| |

| "I

spent most of the summer waiting for the cash to arrive, and just

as I was doubting if it would ever come, it was deposited in my

bank account just as the British season was coming to an end." |

| |

|

“By then I was the owner of a bike reputed to be a Vic Duggan

‘Black Duck.” I always doubted the authenticity of this, but it

was a very fast bike and served me well when I returned to South

Africa.” |

| |

| As a

rider in the South African League, Collins rode for the

Johannesburg-based Wembley Lions, Randfontein Aces, Boksburg Bees

and Springs Stars. “There was also a very fluid guest rider system

operated by Fuller, You could be a regular for example with

Springs, but also be called into action for any of the other teams

if a need arose. |

| |

| “Over

the years, the South African League was very competitive. Riders

like Ronnie Moore, Barry Briggs, Trevor Redmond, Freddie and Ian

Williams, Alan Hunt, Ron Mountford and Basse Hveem were just a few

of the European stars who rode in it.” |

| |

| |

| South Africa 1 |

| |

|

| Courtesy of John Hyam |

| |

|

Dave Collins, extreme left, and the 1949 England team meet the

mayor of Boksburg at a test against South Africa, |

| |

|

Collins pointed out, “And of course South Africa had its own big

stars like Henry Long, Doug Davies, Buddy Fuller, Doug Serrurier

and Trevor Blokdyk proving their worth over the years. At its

peak, the sport probably equalled what was being seen in Britain.” |

| |

| |

| South Africa 2 |

| |

|

| Courtesy of John Hyam |

| |

|

Freddie and Ian Williams with Dave Collins (right) in the pits at

Wembley Stadium, Johannesburg. |

| |

| |

| South Africa 3 |

| |

|

| Courtesy of John Hyam |

| |

|

Henry Long, on bike, and Dave Collins admire a trophy. |

| |

| |

| South Africa 4 |

| |

|

| Courtesy of John Hyam |

| |

|

Dave Collins meets a trophy girl at Springs. |

| |

|

Collins added: “For most of 1951, I did second-half rides at

various British tracks. The sport was very competitive and it was

hard to get chances. But when they came along, you never turned

them down. I remember taking by bike and gear on the tube from

Plaistow to Liverpool Street, then pushing the lot across London

to Paddington just to have a second-half ride at Cardiff.” |

| |

|

The end of the British season saw Collins return to South Africa.

“There the ‘Black Duck’ lived up to its Vic Duggan-legend and I

did very well with it,” he commented. |

| |

|

Collins was back in England for the 1953 season. “At the start of

the season I was given second-half rides at two London tracks that

could not be more different, the 262-yard New Cross and the

440-yard West Ham track. |

| |

|

“From these tracks I signed for Swindon and again was confined to

the second-half. Desperate to get more experience, when the offer

of 10 meetings in Spain came along I jumped at the chance. I later

heard that had I stayed in England, I would have been given a team

chance with Swindon. It’s academic now and the only person who

might have confirmed it was Norman Parker’s wife Jean who ran the

track office.” |

| |

|

Before going to race in Spain, Collins was involved in a Phil

Bishop-managed tour of Holland. He said, “I really enjoyed that

venture. Besides Bishop, others who raced in the Dutch meetings

included Howdy Byford, Pete Lansdale and Roy Craighead - all of

whom had won big reputations over the years with various British

teams. |

| |

| “We

appeared in three wonderful stadiums - the Olympic Stadium in

Amsterdam, at the Feynoord Stadium in Rotterdam, and at Hengelo,

which is up on the Dutch-German border.” |

| |

|

Collins recalls of the period spent in Spain. “The British

organiser was Ted Gibson who rode for several British tracks

during the late 1940s. Even now, the mention of his name and how

he handled the tour sends my blood pressure up a couple of

notches. |

| |

|

“Gibson’s role was to organise things like getting us

accommodation and to the meetings. The promoter was a former

German Luftwaffe pilot Hans Fabry. He owned a Piper Tripacer

aircraft and used to fly from Barcelona to meetings in Majorca

while the riders froze on the deck of a rust-bucket ferry ship.” |

| |

| Dave Collins, Part Two

By John Hyam: - |

| |

|

John Hyam writes about Londoner Dave Collins who went to South

Africa in 1947 to work as a gold miner, started his speedway

career there, then came back to race in Britain and Europe. |

| |

|

In late 1953, South African-based English rider Dave Collins was

part of a British team that went to pioneer the sport in Spain. |

| |

|

| |

1953 - Dave Collins and Vic Ridgeon in Spain.

|

| |

|

Collins has an amusing recollection of the racing-manager Ted

Gibson who fell out with the riders over delays in paying their

wages and hotel expenses.

Collins said of Gibson: “He could not see anything without his

spectacles. When we were in Tarragona one rider - I think it was

Jimmy Wright - hid his glasses. It left Gibson forced to wear his

special racing goggles - these also had lenses like ‘the bottom of

a Coca-Cola bottle.’ Passers-by used to stop and point at him.” |

| |

|

Collins vividly recalls trying to race speedway on the bull rings

in Barcelona, Tarragona and Majorca.

“The racing was exciting and, with no straights, falls were

frequent - usually after the race! Initially, the Spanish people

were disinterested but they soon became very excited by the racing

from us who they dubbed ‘El Suicidos’ - it was magic,” Collins

said. |

| |

| When

the Spanish tour ended, most of the British riders needed

financial help from the British Consul to get home. Collins said:

“I was not involved as I managed to get a lift back to England

with the New Zealand road racing star Ken Mudford and he took me

to Plumstead where he left his bikes for tuning at the AJS

motorcycle factory. I then made my way onto Romford. |

| |

| “There

is no doubt, this Spanish speedway tour was a disaster

financially, but did provide some interesting insight into the

Spanish way of life which, even being then under the government of

General Franco, was a virtual paradise and from that aspect I

really enjoyed myself.” |

| |

| It was

not until 1962 that Collins again tried his luck in England. He

explained: “My mother was seriously ill and I stayed in Romford

for 10 weeks. In that time, I was given the use of a bike owned by

the former Birmingham rider Doug Davies, who had left it with the

engine-tuner Victor Martin. Davies gave me permission to use it

while I was in England. “I was signed to ride for Plymouth

in the Provincial League, but they closed after I spent two weeks

with them. Then I signed for Leicester but before I really got

started I had to return urgently to South Africa.” |

| |

| Leading promoter Mike Parker was the next person to entice Collins

back for another try in British speedway. Collins recalled:

“Parker wrote offering me a team place at Sunderland" . As my pal

Vic Ridgeon was also racing there, I jumped at the opportunity and

travelled over with my wife Val. “It was not a happy

experience. I never really got on with either Parker or his

co-promoter Bill Bridgett. Out of the blue, they just closed down

Sunderland and Val and I were stranded". |

| |

|

| |

| John Skinner says: Dave Collins 1964 (Sunderland

Saints) doing the splits! From the helmet colours I would say this

took place at Wolverhampton |

| |

|

| |

| John Skinner says: A mud spattered Dave

Collins wearing his Sunderland Saints race jacket but John Hyam,

whom supplied the image, says the picture was taken in Durban! |

| |

| “We

decided to ship our Commer Caravan to the continent and travel

around, eventually reaching Gothenburg in Sweden on the night of

the world championship final. That was a highlight of speedway

spectating for me.” Just before setting out for Europe,

Collins raced in a meeting at Rayleigh who were then in dispute

with the Control Board. As a result, Collins and the other

starters at the meeting were branded as rebels. This verdict

soured him permanently against continuing in British speedway. |

| |

|

| |

1964 - Dave Collins and his friend Vic Ridgeon in the Rayleigh

pits.

|

| |

| He

said: “After 1964, I soldiered on in South African speedway. The

most memorable part of that period was in the 1967-68 season when

I was invited to captain the British team in a test match in Cape

Town. “Cape Town is 900 miles from where I was living in

Johannesburg. I finished work at 5pm, rushed to the airport on my

Laverda motorcycle to catch the 6pm flight. When I arrived in Cape

Town, I was met by car and rushed to the outside of the stadium,

then flown into the arena by helicopter. It was a great

experience.” |

| |

|

| |

1960s action at Wembley Stadium, Johannesburg. From the left, Toy

Edwards, Dave Collins and Freddie Williams

|

| |

|

| |

|

1970 - Dave Collins tests a midget car at Wembley Stadium,

Johannesburg. |

| |

| In

South African racing, Collins rode three times for England in the

1949-50 test series and again for the UK in 1967. He also rode in

three tests for Overseas against England in 1953-54 and for the

British team against South Africa in 1971. Besides racing

for a variety of South African league teams, Collins also

partnered Australian star Junior Bainbridge when they won an

International Pairs tournament at Randfontein in the 1954-55

season. |

| |

|

After retiring from speedway, Collins was keen to get involved

with a training school being run by former Wimbledon rider Peter

Murray. “That was soured for me when I heard somebody mutter

something about ‘old riders who will do anything to get into a

meeting for nothing and are out to get themselves noticed.’ At

first, I thought it was a joke but the guy concerned turned out to

be serious. I never went to another practice session.” |

| |

|

Even away from speedway, Dave Collins still sought adventure and

excitement. “In 1972, I joined the South African Volunteer Reserve

Squadron and flew as a pilot with them. When I left in 1984 it was

with the rank of captain, so I feel that was also something of an

achievement.

“But nothing can ever recapture the magic of the years in

speedway. Despite quite a lot of injuries, I would race all over

again. It was a wonderful life.” |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

Hedon Stadium

Hedon Near

Hull |

| |

| John Hyam says:

IT’S amazing! Some of the crazy things you get up to when you are

younger - and sillier. |

| |

|

I tried to be a speedway rider with disastrous results in the

mid 1950s. Before that I was involved in 1954 in an

ill-founded attempt to reopen High Beech as a Southern Area

League track. Finding the stadium in ultra-need of renovation,

no safety fence and the track and the centre green a storage

yard for hundreds of beer crates killed the High Beech revival

idea very quickly.

|

| |

|

But that promotional aspiration was rekindled enough to prompt a

second attempt in 1959 as news came through of the likely start of

a Provincial League in 1960 under the guidance of Mike Parker.

This time the target was Hedon stadium in Hull, a track built at

an old airport on the outskirts of the city which ran in the old

National League Division Three in 1948 and part of 1949, before

the operation moved on to Swindon. |

| |

| |

| Pete Rogers |

| |

|

| |

|

Hull's possible return to the sport for 1960 was the brainchild of

myself and one-time Wimbledon and Oxford second-half rider Pete

Rogers. We had no money - just sheer enthusiasm and a vague idea

of getting ourselves on the promotional speedway chain. It was

late in 1959 when we decided to travel from London to Hull - not

the easiest of places to get to these days from the south of

England. And more so 50 years ago. |

| |

|

And, at was probably the worst time of the year weatherwise, we

decided to go to Hedon Stadium in late November. Some hours out

from London it started to rain. It was on a Saturday night as we

travelled north - I couldn’t drive a car then so the burden of the

outward and return journey fell on Pete Rogers. It was a

nightmare as we battled northwards. |

| |

| We

left London around 9.30 pm and arrived at Hedon at 7.00 am the

next day. Hull probably isn’t the most exciting of cities to visit

- and it was a miserable and unimposing sight on that wet Sunday

morning. |

| |

| Upon

our arrival we scouted around and found the site of the old Hull’s

Angels - a team that had tracked such riders as Mick Mitchell, Alf

Webster, Derek Glover, Johnnie White, Fred Yates, Fred ‘Tracker’

Tracey and Norman Johnson. But we were more than disappointed at

our findings. There was nothing to indicate that a stadium - of

sorts - had been there although we could trace a very visible

outline of what had once been the famous D-shaped Hedon track. |

| |

| |

Alf Webster

Hull 1948 |

| |

|

| |

| |

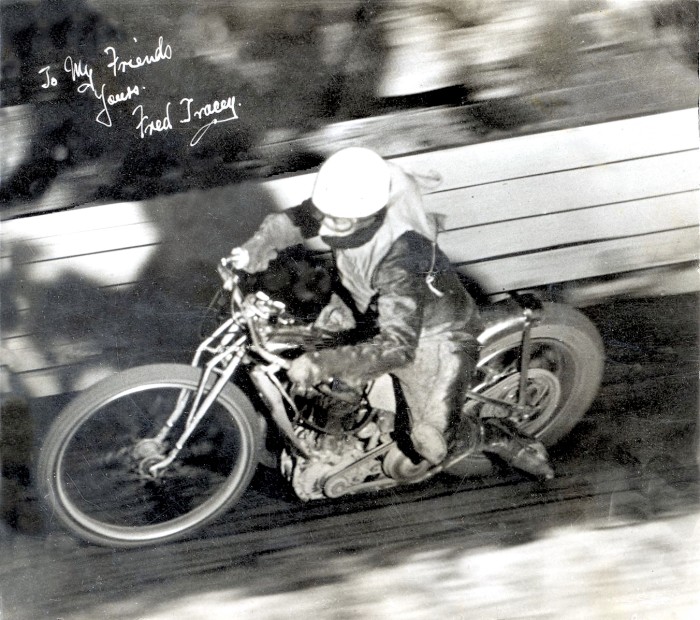

| Hull's Fred Tracey |

| |

|

| |

| |

Hull's

Fred Yates

In Tamworth Colours |

| |

|

| |

| |

| Hull's

New Cross's Mick Mitchell (Right) With

Jeff Lloyd |

| |

|

| |

| Fred Pallett says: Hello John, Just

noticed that the fourth photo from the end of John Hyam Part 4

shows two riders and is captioned "Hull's Mick Mitchell (right)

with Jeff Lloyd". This would appear to be incorrect. I can confirm

that both rode for New Cross, whose colours they are wearing in

the photo. Conversely, I have been unable to find any evidence

that they rode for Hull at any time. For further confirmation,

there are photos of both riders in the New Cross section of

Defunct Speedway. Accordingly, you might wish to amend the caption

in John Hyam Part 4 to read "New Cross's Mick Mitchell (right)

with Jeff Lloyd". |

| |

| John Hyam says: There

then followed the all-too traditional habit of walking round the

track. The surface was sodden, clingy clay of sorts. My shoes soon

let water, then somehow I got bogged down and part of the sole of

one of my shoes was torn away. Pete Rogers walked grimly besides

me - muttering about "getting involved in an idiot’s venture." I

now presume he was referring to me! |

| |

|

Then came rational thought. To go through all the planning

applications to return speedway to Hull, and the financial

outlay involved, would probably be prohibitive. “What are we

doing here?” we wondered as the rain cam down in torrents. It

hadn’t stopped for hours. There was one thing to do - beat a

hasty retreat southwards.

|

| |

|

But before we left Hull, a place I have never been to since, there

was one memorable happening - a traditional English breakfast in a

transport cafe. It was super - and mentally I can still enjoy it

now. After that we made the return journey to London - around noon

the rain stopped. Our promotional plans, like the weather, had

been a washout. |

| |

|

Overall, we had involved ourselves in a 26-hour round trip - and I

had to pay my share of the travelling expenses - I think it was £5

old money. It’s as well other people are able to get into the

promotional side of speedway properly. My record in that direction

is abysmal. However, with the passing of the years they now

provide some amusement. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

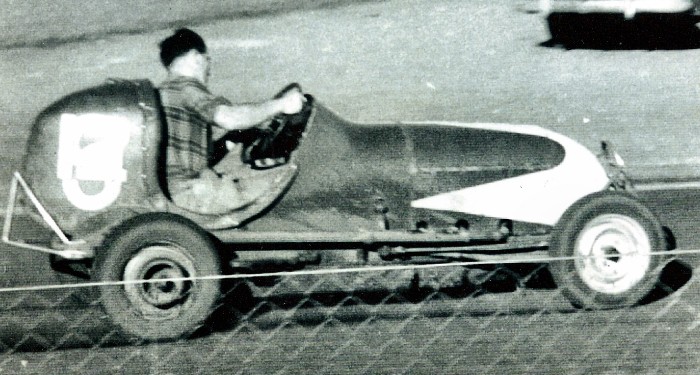

Midget

Cars v Speedway |

| By John Hyam |

| |

|

| A fine example of a Midget Car |

| |

| IT was a unique challenge match and it

took place over 60 years ago at Glasgow's Ashfield Speedway. |

| At the time, while the Ashfield 'Giants'

were doing their stuff in the National Speedway League's second

division, the promotion was also trying to pioneer midget car

racing. |

| |

| Naturally, there was some keen rivalry

between the bikers and the car men. And while the car men could

never be tempted on to two wheels, some of the speedway riders

fancied their chances on four wheels. |

| |

| There's no disputing the cars were 'pretty

lethal.' They were owned by a giant of a man, 17-stone Dave

Hughes, who had trouble squeezing into his car. But while he had

weight problems he could still use craft to win races. |

| |

| The cars, were built by one-handed pre-war

driver Harry Skirrow, who had pioneered them at Belle Vue,

Coventry and Lea Bridge in the late 1930s, were four-wheel drive

with transmission brakes. The engines were JAP twin-996cc,

commonly known as 8/80, with a power output of over 80bhp. They

were of the type used just before the outbreak of war in September

1939 by the late Eric Ferneyhaugh in an unsuccessful; motorcycle

world speed record attempt. |

| |

| Eric Liddell |

| |

|

| |

|

In 1953, Eric Liddell, a Scottish-based speedway

rider, had also built himself a good reputation in midget cars,

but the rest of the Ashfield speedway team were untried on four

wheels. But Liddell put together a squad with Cyril Cooper, Johnny

Green, Doug Templeton and Australian rider Ron Phillips in his

side to race against the midget drivers. NIven MacReadie was the

reserve. The midget team, labelled as Stepps Stadium, was

led by Hughes and included Mark Black, Tommy Forster, Jimmy Reid,

George Ellis. The epic clash took place on Tueday, October

15, 1953, Races were two-a-side, with the familiar 3-2-1-0 points

scoring for finishing places. Races were four laps clutch start.

The match opened with a drawn heat, Hughes leading home Liddell

and Cooper. In the next heat Green and Phillips shocked the car

men at their own game with a 5-1 from third placed Glasgow bus

driver Forster.

|

| |

|

A 4-2 from Liddell, when he split Hughes and Ellis,

kept the speedway men ahead 10-8 after three heats. Then in a

rerun heat four, Black and Forster took a 5-1 over Cooper after

Green went out with engine failure

|

|

And so the midget men 13-11 ahead kept a a slender

lead in the match with their drivers taking first place in the

heats up to eight, when Templeton won and Green was third in a 4-2

result

|

| |

|

Going into heat nine, the car men led 25-23, but

then Liddell and reserve MacReadie took a 4-2 from Reid, and the

scores were tied 27-27. In heat 10, Hughes and Ellis with a 4-2

over Templeton put the speedway riders back in front. And after

two drawn heats, the midget drivers led 37-35 going into the

penultimate race heat 13.In this, a 4-2 by MacReadie and Phillips

over Hughes broke a sequence of midget drivers as heat winners.

And it made the score 39-39 with two races left.

|

| |

|

Interest and excitement was at fever pitch. In heat

14 Templeton and Phillips grabbed a 4-2 from Ellis to give the

speedway riders a 43-41 advantage going into the last race.

Liddell and Phillips lined up for the speedway riders while the

Stepps' midget drivers put out the formidable Hughes-Forster duo.

Liddell swept into the lead with Hughes challenging all the way.

Forster nosed past Phillips but the speedway rider outwitted him

on the last lap and went after Hughes. And that's how it finished,

a 4-2 win for the speedway riders and a 47-43 match victory.

|

| |

|

| |

| Dave Hughes number 66 top scored for the

midget car drivers. Also seen is George Ellis - who pre-WW2 was a

junior speedway rider. |

| |

|

SPEEDWAY RIDERS 47: Doug Templeton 13, Eric

Liddell 12, Niven MacReadie 9, Ron Phillips 6, Cyril Cooper 4,

Johnny Green 3.

STEPPS MIDGETS 43: Dave Hughes 16, Tommy

Forster 10, George Ellis 8, Jimmy Reid 5, Mark Black 4.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The contents of the site are © and should not be

reproduced elsewhere for financial gain. The contributors to this site

gave the pictures and information on that understanding. If anyone has

any issue or objections to any items on the site please

e-mail

and I will amend or remove the item. Where possible credit

has been given to the owner of each item. |