| |

| |

John Hyam

Part 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

The Atom Car

Briggo

Finland's_Antti_Pajari

Southampton's Boys From The Black Stuff

Midget Car Carnage |

|

Wimbledon Speedway

Keith Harvey

Split

Waterman/1952 Golden Helmet |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

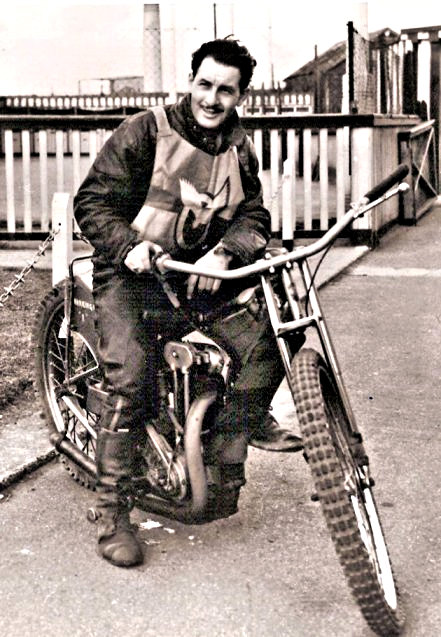

Long-time speedway journalist and photographer John Hyam. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Split

Waterman

& The

1952

Golden Helmet |

|

|

|

|

|

|

John Hyam says:- |

|

PEDESTRIANS outside the Royal Automobile Club’s offices in

London’s Pall Mall were forced to move aside on a sunny

afternoon in July 1952 by four Harringay supporters carrying

placards reading "Fair Play for Split Waterman." |

|

|

|

It was part of Waterman's protest at what he regarded was unfair

treatment in regard to the 'Golden Helmet' match race

championship, then the biggest prize in British speedway after the

world championship. |

|

|

|

The hearing on July 8 1952 eventually found against Waterman, who

was legally represented, for refusing to race against Jack Young

after falling in the first heat of their challenge at West

Ham on June 24. It had been a controversial championship event. In

the first race, Waterman fell when Young went inside him. In the

rerun Waterman was an easy winner. |

|

|

|

Then, to the amazement of Waterman and an 18,000 crowd, it was

announced that there would be a third race to decide the leg - the

first race having been awarded to Young because of Waterman

falling. Waterman refused to accept this decision and withdrew

from the challenge. For this he was reported to the Control Board

and severely reprimanded. |

|

|

|

However, the fracas at Custom House was all part of a long-running

saga involving Waterman and the ‘Golden Helmet’ going back to him

winning the championship from the holder Belle Vue’s Jack Parker

in August 1951 and subsequently beating his first 1951 challenger

Aub Lawson of West Ham. |

|

|

|

The problems came the following season. In April, Waterman made a

successful defence against Young, and the following month was due

to defend against Wimbledon’s Ronnie Moore. However, Waterman was

forced to withdraw from the tie and the championship was declared

vacant. This was in accordance with a Control Board rule that if a

champion was unable to defend within four weeks of his previous

defence the title would be declared vacant. |

|

|

|

The crucial dates were that Waterman had defeated Young in the

second leg on April 25 and was set to face Moore for the first

time on May 26. He asked for dispensation of one week to recover

from injury. He then went on to meet Young for the vacant title in

June which resulted in the controversy. An appeal by Waterman and

Harringay about what happened at West Ham was rejected by the

Control Board. The subsequent Board hearing, at which Waterman

engaged the placard supporting Harringay fans, found him guilty

and he was ‘severely reprimanded and warned as to his future

conduct.’ |

|

|

|

The passing of the years, however, endorses the fact that Waterman

was harshly treated and should, in all probability, have won his

appeal. It is now known that an announcement was made to the crowd

that the first heat between Waterman and Young would be rerun,

whereas the referee had already made a decision to award the race

to Young. |

|

|

|

When the race was restaged, both riders started off the same gates

as they had in the unfinished heat. If the restaging had in fact

been a bona-fide second race both riders, according to he rules,

should have started off alternate grids. |

|

|

|

The award of the race to Young brought to light more conflict in

regard to the referee’s action. Under the rules, if the race had

been stopped because it was felt a rider was in danger it should

have been restarted, while if Waterman was the cause of the

stoppage he should have been excluded from the restart. |

|

|

|

Over the years, the evidence makes it clear that Waterman was

unfairly treated. For its part, the Control Board seemingly

ignored what evidence there was in Waterman’s favour, and it looks

substantial, making a decision that, to put it mildly, very

harshly treated the Harringay star. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Atom Car |

|

|

|

Allard Midget Cars |

| |

|

| Courtesy of John Hyam |

| |

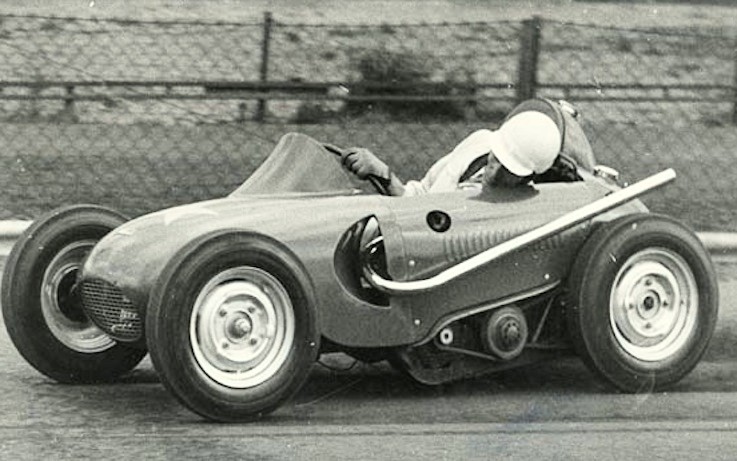

| Cyril Brine at Rayleigh testing the 1955

Atom Car |

| |

| John Hyam writes:

In the mid-1950s, stemming from Wimbledon speedway, there was an

effort to popularise midget car racing as a part of the

second-half of speedway meetings. |

|

|

|

Former Eastbourne and Wimbledon rider Alan Brett, who was involved

in the venture, recalls what happened in regard to what were known

as the Allard Midget Cars. He said, “I remember them well and

world speedway champion Ronnie Moore turning one over at practice

one Tuesday morning and breaking his collar-bone. |

|

|

|

“At the time, I lived in a flat at Wimbledon that had previously

been the home of Trevor Redmond, who was also keen on midgets as

well as his own speedway career. The main developers of the Allard

car were Stanley Allard and Charles Batson.” |

|

|

|

Years later, Chris Humberstone of Allard Motorsport said, “A

meeting between Stanley Allard and riders and management was held

at Wimbledon to discuss the possibility of building a small car

for use on the dirt. |

|

|

|

“The popularity of speedway racing was waning at that time and it

was thought that, perhaps, car racing would bring back the crowds.

Mr Gill Jepson was called in and working from a few pencil

sketches by Sydney, he built up a chassis, using light

channel-selection steel. It had a 3ft front track and a straight

tube axle mounted with two quarter-eliptic springs and radius

rods, while the rear was unsprung, using an axle-tune mounted

between thrust races on each side of the frame.” |

|

|

|

Humberstone explained, “The rear track measured 2ft 9in, and the

tiny wheelbarrow wheels were driven from the centrally mounted

engine by chain and sprockets. As with the speedway bikes, there

was no gearbox, but a final-drive shaft sprocket was designed for

easy removal to permit quick changes of ratio. |

|

|

|

“The wheelbase was 4ft 6ins and the completed car and it light

aluminium body weighed just 278lb. Painted in bright colours and

named “The Atom”, it was put on a raised dias at a Wimbledon

speedway meeting, and shortly in October 1955 after was tested on

an empty track by speedway star Ronnie Moore. |

|

|

|

“It went quite well, though suffering from insufficient head of

petrol from the tail-mounted gravity-feeding tank. A pump was

fitted, driven off the axle shaft and performance was much

improved,. But after several laps Moore overdid things on one

corner and the car overturned with him breaking his collar bone.” |

|

|

|

Humberstone concluded, “Not surprisingly, his interest waned a

little after that and as further tests at Rayleigh with another

Dons' rider Cyril Brine driving showed that passing would be

difficult and the first man away would usually win, the idea was

dropped.” |

|

|

|

Gil Jepson, who played a major role in designing ‘The Atom’ added,

“It was fitted with a JAP speedway-type engine, but the problem

was with the springs which were similar to those used in the

Frazer-Nash racing sports car. Even on the straights these tended

to cause a sideways movement. |

|

|

|

“Ronnie Moore had problems when testing the car and generally we

decided that the project was not suitable and the venture was

abandoned.” |

|

|

|

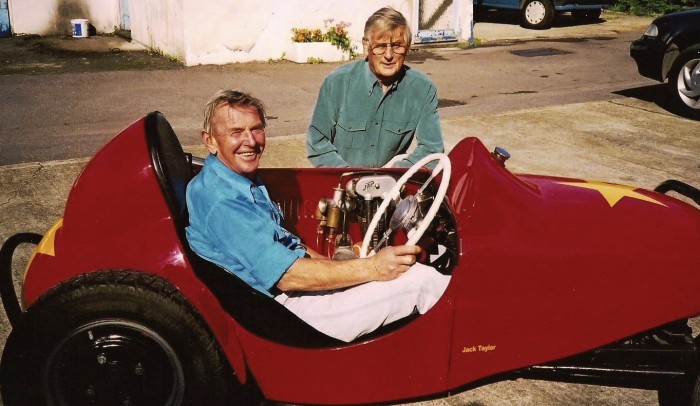

In 2002, thanks to the efforts of Reg Fearman, Ronnie Moore

was reunited with 'The Atom' when he was taken to meet its

owner, the former Aldershot and Eastbourne rider Jack Taylor.

|

|

|

|

As a footnote, in the same period as the Atom Car trials were

being held at Wimbledon, other tests were taking place at Rayleigh

where Dons’ captain Cyril Brine was the driver while his brother

Ted looked after the mechanical side. |

|

|

|

|

Ronnie Moore

In The Atom Car |

| |

|

|

Courtesy of John Hyam |

|

|

| |

| Ronnie Moore Reunited With The Atom Car |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ronnie Moore is reunited with the Atom Car. Also seen is the car's

owner, former Aldershot and Eastbourne rider Jack Taylor. The

photo was taken by Reg Fearman. |

|

|

|

John Skinner says: A great photo showing the JAP engine mounted in

the centre of the car alongside the driver. Health & Safety

would probably rule this out in modern times. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

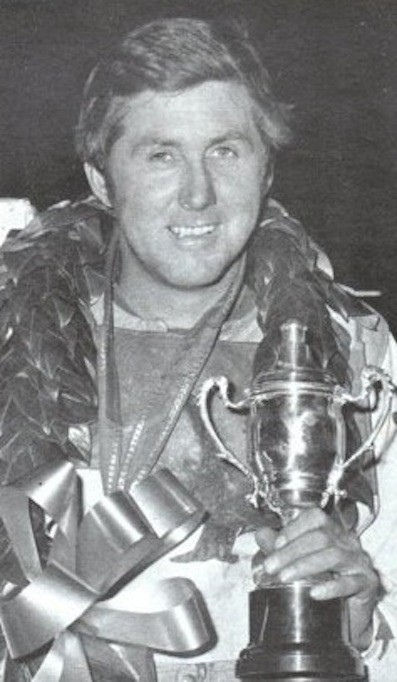

Barry Briggs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Barry Briggs in 1969 |

|

|

|

It is amazing the topics that come up for discussion when you are

traveling home from a speedway meeting. |

|

|

|

A case that often springs to mind was a journey from Oxford to

London with Barry Briggs. I cannot remember much talk taking place

about speedway, but I still recall the passionate interest we both

had at that time in the American nuclear-powered submarine USS

Nautilus. |

|

|

|

It was in October 1958, and we were both enthralled at the bravery

of the crew and their exploits earlier that year. Just to refresh

the topic: the submarine left its Pacific Ocean base at Pearl

Harbour in Hawaii on July 28 1958. It then went through the

Bering Straight and under the Arctic ice to arrive at the

geographic North Pole on August 3. From there, the submarine

continued its journey to Portland on the south coast. |

|

|

|

At the time, I was collaborator with Briggo on a series of

articles that appeared under his name in 'Speedway Star'. Often, I

needed to share a topic with him, but I am certain that our chat

about the Nautilus never got an airing. |

|

|

|

I first became deeply involved with Briggo in 1956, when he opened

a record shop in Mitcham and part of the deal for his article was

a contra-advert in the 'Speedway Star.' In those days,

rider-articles were a popular part of speedway journalism and

'first person' articles were greatly loved by the Star's readers. |

|

|

|

Others who I worked with in a similar capacity included the

Swindon riders Neil Street (a really wonderful man) and Ian

Williams, as well as the Ipswich rider Bert Edwards. In the latter

1950s, I also co-operated with that great old-timer Phil Bishop on

a series about his pre-war memories. |

|

|

|

I doubt very much if modern speedway fans would have much interest

in works of this type. But the world was then a very different

place. On reflection, I think that, in many ways, the speedway of

the 1950s and early 1960s was a much different sport to that

presented in these modern times. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Briggo riding for Southampton |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Keith Harvey

South

African |

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of J Spoor |

|

|

|

BY JOHN HYAM |

|

|

|

I became interested in Keith Harvey in May 1946, the year that I

discovered speedway. He was signed by New Cross and the item by

Jim Stenner in the London 'Evening News' surprised me. It said

Harvey, the pre-war captain of the 1939 Crystal Palace team, was

to make a come-back for New Cross at the aged of 50 years. I was

then 13 years old and my father was just 44 - I could not believe

there was a speedway rider anywhere older than that! |

|

|

|

Harvey was a South African who started riding speedway when he

arrived in England in 1928. He was a well-known motorcycle rider

in his homeland - he took part in a 500-mile race sometime in the

early 1920s and was among the finishers in a snowstorm. |

|

|

|

I next read an item on Harvey in a book by Eric Linden. This said

he did not get on to a speedway bike until he was 32 years old,

but in the sport's early days had been 'one of the showmen

legtrailers' at Stamford Bridge. Pre-war he also rode for teams

including West Ham, Wimbledon and Birmingham. |

|

|

|

In 1939 he rode for Crystal Palace in their brief spell in the

National League Division Two. When they closed in mid-season he

signed for Norwich, to whom he was allocated in the post-war rider

pooling in 1946 but never rode for the Stars. In 1946, as a New

Cross rider Harvey varied between being the first reserve and

sometimes in the full-team, where most times he was partner to Ron

Johnson. Harvey started the 1947 season as a New Cross rider, but

the advent of younger riders like Ray Moore, Jeff Lloyd, Ken le

Breton, saw him drop down to the second-half. He made his last

appearance before retiring in June that year. |

|

|

|

Eventually, Harvey returned to South Africa and lived in Durban,

where he was a frequent visitor to the pits of the famous Durban

Hornets. In pre-war years he was probably South Africa's best

known speedway rider. Ironically, Harvey never raced on a speedway

in his homeland. |

|

|

|

Keith Harvey died in 1972 and was buried in his home town at

Verulaam. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Antti Pajari

Finland |

|

|

|

|

|

|

On a dramatic night when he made his first London appearance in

early 1959, Finnish rider Antti Pajari gave new meaning to the

phrase 'spectacle.' |

|

|

|

To say that his trackwork was 'wild and wooly' is putting it

mildly. Pajari just wrapped on the throttle and kept going at

full-blast. He had just been signed by Coventry and they chose to

parade him before Wimbledon's discerning fans. |

|

|

|

The older Plough Lane spectators had not seen anything like the

Finn's 'scrape the safety fence' style of riding since the early

post-war seasons when Oliver Hart and Lloyd Goffe had given them a

taste of 'hold-on-for-dear-life' riding. |

|

|

|

He was the first Finnish rider to appear on a British track, and

actually was Coventry promoter Charles Ochitree's second choice of

taking a rider from this speedway outpost. First in line had been

Timo Laine who. in the 1957 and 1958 seasons, had emerged as a

leading performer in European racing. |

|

|

|

Laine was not a 'no hope' foreigner but a performer of great style

and ability. The legendary Australian rider Jack Young once summed

Laine up to me as 'a really class act.' But, like so many

Scandinavians, Laine was also heavily involved in the lucrative

European long-track scene. And the money to be made there was more

than could be gained from just concentrating on speedway. |

|

|

|

For some months during the 1958-59 winter, I was an "unofficial

go-between" for Ochiltree with Laine's agent. When his asking

price to join the Bees was not met, up came the name of Antti

Pajari. I was told, "He's not such a smooth rider as Laine, but

you'll find he is fast and fearless." As was subsequently proved

after he finally settled for a deal to race a full season for the

Bees, that was something of an under statement. Fear when on the

track didn't seem to be part of the Pajari scheme of things when

racing. |

|

|

|

He arrived in England at Easter 1959, on the back of a reputation

of being his country's national champion in the 1956, 1957 and

1958 seasons. That didn't mean a lot, because there was no

yardstick to assess Finland's race standards against those in

Britain. But, with the opinion of Coventry's one-time Swedish Peo

Soderman also singing his praises, Pajari was a new kid on the

block for the 1959 season. |

|

|

|

When he turned out for the Bees at Plough Lane and demonstrated

his fence-scraping despite not scoring a point, Pajari made the

headlines in several daily newspapers the next day. The Fleet

Street brigade however made one glaring error - they described

Pajari as 'the Turkish speedway champion. Perhaps it should have

been 'The Flying Finn'! |

|

|

|

Off the track, Pajari was a colourful, hard drinking character.

His special love was vodka - and it didn't seem to affect him, no

matter how many he downed! At Coventry, Pajari became an adequate

and ever-improving second string rider with the ability on some

nights to be among the top scorers. |

|

|

|

When the end of the season arrived, Pajari had done enough

with a near five points average to convince promoter Ochiltree

he was a must for the 1960 season. But Pajari's British

reputation had preceded him to the continent, and the lure of

big money earnings on the long tracks - which over the years

deprived British speedway of stars like Norway's legendary

Basse Hveem and the German aces Josef Hofmeister and Egon

Muller - also attracted Pajari. |

|

|

|

Pajari held out for terms that Coventry declined to meet. It

meant that the Finn slipped out of the Coventry scheme as a

one-season wonder with a budding talent that was not to be

seen again on a British raceway. Some experts went so far as

to say the rider's decision to stay out of British speedway

prevented him from probably claiming the honour of eventually

being the first Finnish rider to appear in a World

Championship final. |

|

|

|

In Europe, Pajari increasingly contested the big long-track

and grass track meetings with their high pay rates. In the

early years of the 1960s, speedway became a second-fiddle to

his motorcycle activities. His name, however, appeared

regularly as one of his country's leading riders in both world

championship and World Team Cup meetings until 1965, when he

retired to join fellow countryman Timo Laine in the

spectacular world of power boat racing. |

|

|

|

Pajari's departure from British speedway came at a time when

the sport was very much in recession and was in dire need of

riders with his breath-taking and forceful style to keep the

turnstiles clicking. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The "Boys

From The

Black Stuff" |

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of John Hyam |

|

|

|

Mike Tams in Newcastle Diamonds Race Jacket, Ern Brecknell centre

and

Brian McKeown |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Australian Ern Brecknell pictured in Newcastle Magpies livery |

|

|

|

They don't make 'em like this anymore! And that's a pity! Three

of the most colourful perormers for Southampton in 1952 and 1953

were Ern Brecknell (Australia), Mike Tams (Canada) and Brian

McKeown (New Zealand). |

|

|

|

When they weren't on track scoring points for the Saints, the trio

worked part-time laying tarmac on various road building schemes in

the south of England. Off-track, they were a hard living but

kindly trio and enjoyed something of a folklore reputation with

Baninister Court fans |

|

|

|

One anecdote I like about them is that, to help defray the cost of

paying rents, in the warmer summer months they would 'camp out'

under the Southampton grandstand. When the colder autumn and

winter months arrived they decided to "go indoors". |

|

|

|

This was done by them buying a small garden shed and erecting it

as their living quarters in a far corner of the Southampton car

park. It was not a venture fully approved of by their promoter and

stadium owner Charlie Knott. But he never gave them an eviction

notice. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Midget Car Carnage |

|

|

|

Gerry Hussey & Jack Parker |

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of John Hyam |

|

|

|

West Ham's Gerry Hussey |

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of John Spoor |

|

|

|

Gerry Hussey leading Arthur Forrest on two wheels, but Gerry was

bitten by the four-wheeled bug too. |

|

|

|

John Hyam says: Speedway

riders have long had a grim fascination with midget cars. And for

two riders there were serious repercussions. |

|

|

|

Gerry Hussey, then just 26

years old and hailed as being speedway's greatest find of the

1950s, died racing a midget car at Rowley Park Speedway in South

Australia on March 6 1959. In the crash, Hussey was pinned under

his car and died from his injuries the next day. His nearest

rivals in the race were programmed as L Inwood and R Talbot.

Before that, in December 1957 Hussey had his first major speedway

accident at Rowley Park, sustaining concussion and a back injury. |

|

|

|

Hussey was an English

international who had ridden for West Ham, Norwich and Leicester.

Although racing in the British season, Hussey had moved to

Australia at the end of 1956 season and planned to switch from

solo riding to midget car racing. Hussey had burst on the British

speedway scene in 1953 when, after a serious of top performances

at junior track Rye House, he signed for West Ham. His first match

for the Hammers was in a 42-42 drawn challenge match at Leicester

on October 2. He won his first race and had two second places, but

fell in his last outing. |

|

|

|

Fatal midget car accidents

were not unknown at Rowley Park. A few weeks before Hussey died,

two other drivers lost their lives there in 1959. Steve Howman

died in a crash on January 2, then on January 23 Arn Sunstrom lost

his life in a midget car pile-up. |

|

|

|

Besides his love of speedway

bikes and midget cars, Hussey also rode in the 'Globe of Death' at

Australian fair grounds wearing his England international race

jacket. |

|

|

|

Seven years before Hussey's

fatal crash, the legendary Jack Parker sustained serious injuries

when he ploughed Frank 'Satan' Brewer's midget into the safety

fence at the Sydney Sports Ground in New South Wales - a track

Parker once described as "the best speedway track I have ever

raced on." |

|

|

|

Hussey was a charismatic

personality, who soon endeared himself to the fans. With his

handsome looks, he was the speedway pin-up of the mid-1950s. |

|

|

|

When West Ham closed, Hussey

moved on to Leicester and was equally a big favourite with home

and opposing supporters. To put it frankly, you just could not

help but like him. At West Ham, he came very much under the

influence of twice world champion Jack Young, while another who

helped him on the road to fame was veteran Leicester rider Jock

Grierson. |

|

|

|

Young and Grierson were

influential in taking Hussey to race at Kym Bonython's Rowley

Park. He soon struck up a friendship with Bonython who, besides

holding the promotional reins was also one of Australia's top

midget car drivers. Hussey was fascinated by the powerful four

wheel racers and made it clear that his ultimate intention was to

switch permanently from to two to four wheel racing. |

|

|

|

|

Gerry Hussey

Midget Car Fatality |

|

|

|

Courtesy of John Hyam

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

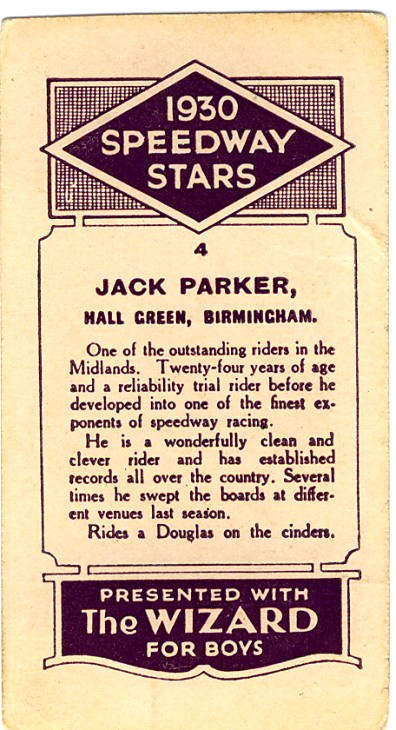

Jack Parker

Midget Car Driver |

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of John Hyam |

|

|

|

Jack Parker driving the legendary Frank 'Satan' Brewer's midget

car in Sydney. |

|

|

|

|

|

Jack Parker had been

fascinated by midget cars since pre-World War Two years, and was a

regular visitor to Coventry when meetings were staged on the

Brandon oval between 1937-39. But he always resisted the

temptation to get behind the wheel of one until February 13 1952. |

|

|

|

Then, Parker got into what was

probably the fastest car in midget car racing at that time. It was

a Ford V860 owned and raced by Frank Brewer, was a top performer

not only in his native New Zealand but Australia, the USA and

England. Brewer was also a keen speedway bike race fan. He knew

Parker especially well from the post-war Australian seasons when

meetings featured races - separately - for bikes, sidecars and

midgets, |

|

|

|

Parker eventually bowed to

temptation and decided to try his hand in a midget car when

offered the chance to compete in a match race against leading

driver 'Bronco' Bill Reynolds. Brewer agreed to help Parker

prepare for the event. It ended in a crash that nearly cost Parker

his life. Australian historian Brian Dalby gave me these details

of Parker's ill-fated crash at the Sportsground. |

|

|

|

Dalby said, "The crash

happened during a test run. There was a momentary lapse of

concentration by Parker and it caused the V8 powered midget to

pitch into a series of rolls and end up buried in the fence with

the driver still behind the wheel, but seriously injured. |

|

|

|

"Parker was expected to die

and remained critical for some time afterwards. The inadequate

helmet of the times left him with a fractured skull as well as a

badly broken arm and scalding from the burst radiator." |

|

|

|

|

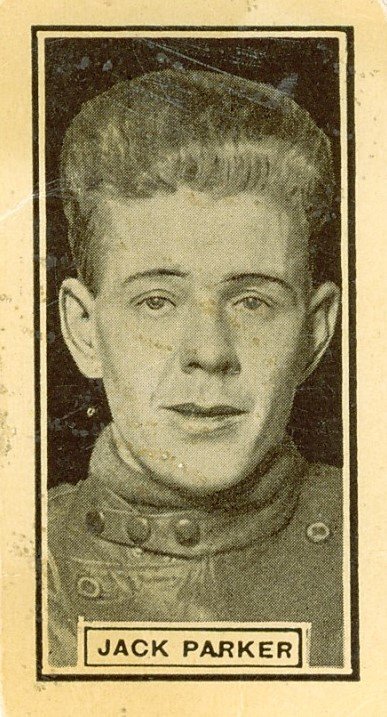

Cigarette Card scans courtesy of John Spoor . Jack was one

of the pioneers of speedway |

|

|

|

Darby added, "In time, Parker

recovered and returned for three more seasons at Hyde Road in

1953 and 1954 but his edge had finally been blunted and he retired

at the end of the 1954 season. Hardly surprising really for a man

approaching 50 in such a physical sport." |

|

|

|

Another speedway rider who had

a serious accident driving a midget car was Wimbledon and New

Zealand star Ronnie Moore. He overturned a midget during a

practice run at Wimbledon in October 1955, and suffered a broken

collar-bone. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wimbledon Speedway |

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of John Spoor |

|

|

|

This article, the first of two parts, was published in the South

London Press on Friday June 7, 1991 to coincide with the closure

of Wimbledon Speedway.

Wimbledon Feature

Part 1

The headlines read:

Small crowds and huge losses mean that for Wimbledon

Speedway it is the...

End of the Roar!

Wimbledon Stadium staged its final

speedway meeting this week - after a colourful history which

stretches back 63 years. In

today’s South London Press John Hyam - who went to his first

speedway meeting in 1946 - looks back at the magical moments which

helped make Wimbledon one of speedway’s top clubs.

The final part of his special feature will be in Tuesday’s paper.

THE lights dimmed on a south London sporting tradition this

week when Wimbledon staged its last speedway race.

After 63 years - interrupted on by World War Two between 1939 and

1945 - the tapes have risen for the last time at Plough Lane.

Wimbledon

was the sport’s oldest surviving speedway stadium - although

fittingly perhaps last Wednesday’s visitors Belle Vue are

speedway’s oldest club.

Both teams can trace their origins back to 1928, when the sport which

started in Australia, then spread to this country.

But although Belle Vue started a few months before Wimbledon, they

moved to a new stadium in Manchester a couple of years ago.

During the 1980s Wimbledon’s future was threatened on a handful of

occasions, but the sport survived.

This time though there is no knight in shining armour poised to

bring a speedway salvation at Plough Lane.

At

the end of the month, the club will start racing on either Fridays

or Sundays at Eastbourne - a track owned by 1960s Dons’ rider

Bobby Dugard.

The

Dugards have had links with Wimbledon since 1946, when Bobby’s

father Charlie had a brief spell in Dons’ colours.

Ironically,

Charlie’s Wimbledon career ended when he crashed with West Ham

rider George Bason. The accident left both men with broken legs

and happened only after they had been involved in an exchange

transfer deal. For a couple of days before being sent home, they

were in adjoining beds at nearby St George’s Hospital.

In

the late 1970s, Bobby’s younger brother Eric had a brief spell in

Wimbledon colours - on loan from Eastbourne, which had been bought

freehold by Charlie in 1947.

Bobby has given Dons a special low rent to continue operations at

the Sussex track and they will be known as ‘Wimbledon at

Eastbourne’ until the end of the season.

The long term future of the club depends on how things work out

during the next few months.

Wimbledon’s current troubles are a long way from the many years of

speedway that has thrilled, delighted and amazed followers of the

sport.

Some

will say the rot at Plough Lane set in when spectacular young

Swede Tommy Jansson was killed while competing in his homeland in

a mid-1970s World Championship qualifying round.

Courtesy John Spoor

Tommy was a real personality who drew the fans, and after his

death much of the magic and attendances went out of meetings at

Plough Lane.

There

are others who will see speedway’s decline on the decision to

switch from the high standard British League, with its colourful

international stars, to the more domesticated National League in

the mid-1980s.

On the other hand, had the club not lowered its standards then,

there may not have been a further six seasons of racing at Plough

Lane.

Tommy Jansson’s death though was, in my opinion, the beginning of

the end for speedway at Wimbledon - even if it took some 15

more seasons for the end to finally arrive.

Tommy is not the only Wimbledon rider to have been killed on the

track. Back in 1937 Reg Vigor, who had been on loan to

Wimbledon’s nursery track at Bristol, died in a horrific smash and

in 1952, Italian-American Ernie Roccio, a great crowd pleaser was

killed at West Ham.

Wimbledon

have had links with American speedway riders since the mid-1930s,

when Miny Waln and Byrd McKinney briefly raced for them in 1937.

Then came the legendary Wilbur Lamoreaux, one of the sport’s

all-time greats. He was later joined by New Yorker Benny Kaufmann

- who could race as fast as he could talk!

Also another familiar figure around Plough Lane in the late 1930s

was the dapper little Texan with the Spanish-sounding name Manuel

Trujillo, who is still regarded as one of speedway’s most

spectacular ever riders and, unlike his fellow North

Americans who pioneered the now conventional foot-forward style,

Trujillo leg-trailed more spectacularly than anyone else.

When

speedway restarted in 1946 after the war, riders were pooled and

Wimbledon were allocated Oliver Hart, whose leg-trailing

broadsiding skill was enough to lift one’s heart into the mouth.

Lloyd

Goffe was another of the great, spectacular leg-trailers who

carved a niche in Wimbledon colours in the post-war seasons,

before moving on for spells with Harringay and St Austell.

In 1947, Hart moved on to Bradford in a three-way transfer that

took Australian Bill Longley back to his pre-war club New Cross

and their star Les Wotton to Wimbledon.

|

|

End of part 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Well Respected Wimbledon Promoter Ronnie Greene |

|

|

|

|

Courtesy John Hyam |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Originally published in the South London Press, on Tuesday

June 11, 1991:

Wimbledon Feature

Part 2

By John Hyam. The headlines read:

End of the Roar!

John Hyam takes a final look back at the

personalities who have graced the Dons' track

In its 63 years at Wimbledon Stadium,

speedway produced many colourful personalities - some were big

stars, others just honest-to-goodness personalities.

One such personality was post-war Dons’ rider Phil ‘Tiger’ Hart,

who was born in nearby Balham and went on to become a millionaire.

In 1926, aged 16, he emigrated to Australia, saw speedway and took

up the sport. He was with the first wave of Australians to arrive

in Britain in 1928, and when England versus Australia tests

started in the 1930s, Hart was selected for Australia - until

somebody pointed out that he was an Englishman.

His spell at Plough Lane was brief, and he spent most of the

pre-war years racing for tracks in the Midlands.

In 1948, Wimbledon paid Birmingham £1,000 for his transfer, but

tragically in his first race back at Plough Lane, Hart crashed,

broke his leg and retired from the sport.

Vic Duggan was an Australian who many claim was his country’s

greatest ever rider, although he never won the World Championship.

While his greatest triumphs were at another departed London track,

Harringay in the mid-1940s, he started his British career with

Wimbledon in the immediate pre-war seasons.

This is Wal Morton and Geoff Pymar in 1957

Ivan Mauger was another of the sport’s greats who started at

Wimbledon as a 16-year-old in 1956.

It was only six years later when Mauger returned to ride for

Newcastle that he started showing the form which was to make him

one of speedway’s great world champions.

Ronnie Moore was another New Zealander who won the world

championship. He came to England in 1950 with his father Les, also

a rider.

Les failed to impress in trials at Plough Lane, but Ronnie became

the club’s first world champion and one of Wimbledon’s best-loved

stars.

While Les failed to get a Wimbledon place, he did form a unique

team partnership with Ronnie at Shelbourne, on the outskirts of

Dublin, which was Dons nursery track in the 1950s.

It was from there that Wimbledon found an outstanding Irish star

in Dominic Perry - who quickly became known as Don Perry.

Shelbourne was also the training ground for another young New

Zealander, Barry Briggs in the 1950s. Like Moore and Mauger, he

also became one of speedway’s great world champions.

Another New Zealander who made a terrific impact on the sport in

this period was Geoff Mardon - fittingly described as an

‘uncrowned world champion.’

In pre-war years - from 1929 to 1939 - in what was then the

National League, Wimbledon made little impact on main events and

only won the title once.

But in the 1950s and 1960s came their greatest run with seven

championships over an eight season period.

Wimbledon’s move to Eastbourne in early 1991 has a parallel to

1948, when their own track temporarily based a ‘foreign team.’

It was the year of the Olympic Games, and for six weeks Wembley

raced their home matches at Plough Lane.

In

the heady post-war years, London derbies sustained speedway and

Dons, who raced on Mondays, had regular away matches at West Ham

(Tuesday), New Cross (Wednesday), Wembley (Thursday) and Harringay

(Friday). The only ‘out of town’ matches were on Saturday, either

at Belle Vue (Manchester) or Bradford.

Americans

have always been popular at Wimbledon. In later pre-war years it

was Wilbur Lamoreaux and Benny Kaufmann. In post-war seasons there

was Ernie Roccio, Brad Oxley, Gene Woods and Bobby Ott. And

pre-war came Canadians Goldie Restall and Crocky Rawding, while

their fellow countryman the formidable Jimmy Gibb was a Don in

1949 and 1951.

Mind

you, there have also been great English riders of world standard

at Wimbledon. Post-war favourite Norman Parker for instance who in

1939 had been at Harringay with his brother Jack.

The

latter was the big post-war star at Belle Vue and his tussles with

Norman in the early post-war match race championship races were

epic, no-quarter given events.

Stylish Midlander Alex Statham, another pre-war Harringay star, the

Buckinghamshire farmer and publican Ron How who won his laurels in

the 1950s, coupled with Bobby Andrews, Cyril Brine,

Split Waterman and Dave Jessup are others accepted as top stars.

|

|

|

|

The website's

John Skinner says: I am a Northerner (a Newcastle Diamonds fan)

but have always enjoyed watching Wimbledon starting in the 1960s and followed their

results and articles in the speedway press because they always had

attractive riders. My thanks to John Hyam for sending me

this two piece article about the Dons. John (Hyam) reviewed a book on the

Dons which I have been able to reproduce below |

|

|

WIMBLEDON DONS

The story of Wimbledon Speedway

Edited by Howard Jones

106 pages, More than 200

photos

£15.99 (post free) from (cheques/postal

orders only)

Speed-Away Promotions, 19,

Arundel Road,

Lytham St. Annes, Lancashire FY8

1AF. |

|

|

|

This book on the Dons by Howard Jones, which I

reviewed as far back as 2008, is an invaluable

item for die-hard Dons' fans to add their

collection. This is how I reviewed the book at the

time of its publication. On the other hand, if you

have a copy of Howard Jones' book what is your

opinion of the work? |

|

|

|

John Hyam says:

MY beginnings with speedway at Wimbledon are

unique. The first match I saw at Plough Lane

on Thursday April 29 1948 actually featured

Wembley Lions beating Belle Vue 52-31 in a

National League match. This was because Wembley

were based at Plough Lane for six weeks while the

Empire Stadium was in use for that year's Olympic

Games. But I had seen the Dons in action many

times when they were visitors to my first speedway

love, the now gone but not forgotten New Cross

team. Their exploits were chronicled earlier this

year in the intriguing 'Out Of The Frying Pan'

(Norman Jacobs).

|

|

|

|

Over my formative speedway

years in the late 1940s, New Cross were often

compared with the Dons - and for most of the time

until their closure in early 1953, New Cross held

sway over their south London rivals, as they had

also done in the pre-war seasons between 1929-39. |

|

|

|

Unlike Norman Jacobs' work, the new Wimbledon book

deviates from a subjective chroniclesiation of the

sport's history at Plough Lane. Rather it

concentrates on a period from the 1950s through

until the demise of top class racing at Plough

Lane on June 5 1991. This is largely in

statistical and pictorial format. |

|

|

|

Many Wimbledon

supporters blamed the stadium bosses the Greyhound

Racing Association for the end of speedway at

Plough Lane in 2005, But speedway had been in

decline for some years before that, and there were

fears as far back as 1986 that the sport would

fold. |

|

|

|

On a happier note, in regard to the book:

it has a bright modern feel, and there are many

great team photos capturing sides as far back as

1931, encapsulating such great names as Vic

Huxley and Ray Tauser. There were also photos of

the two riders who I regard as being the most

spectacular in post-war years to have worn the

club's race-jacket, that great legtrail-style

rider Oliver Hart and the hustle-bustle

thrillmaker Lloyd 'Cowboy' Goffe. In the days when

tracks were deep cinder surfaces rather than the

shale of modern times, their spectacle has never

been reciprocated on the more modern slick

shaleways. |

|

|

|

In analysis, I found the 'Wimbledon

Dons' book absorbing, especially the interviews

with the great 1950s stars Ronnie Moore and Ron

How, and also with multi-world champion Ivan Mauger,

who briefly flirted with a Plough Lane career in

the late 1950s. For lovers of Wimbledon

speedway - and I brand myself as one of them -

"Wimbledon Dons' is an essential addition to a

speedway library. It has a modern feel about and

brilliantly itemises statistics and facts about a

golden era not only for Wimbledon Speedway, but

British speedway generally.

It gives an insight

from the days when speedway was a mainstream sport

through to the lesser dimensions of the present

decade with the ill-fated venture into Conference

League racing between 2004-05. The book gripped

my attention and joins a growing batch of speedway

books in my bookcase. Deservedly so, too.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The contents of the site are © and should not be

reproduced elsewhere for financial gain. The contributors to this site

gave the pictures and information on that understanding. If anyone has

any issue or objections to any items on the site please

e-mail

and I will amend or remove the item. Where possible credit

has been given to the owner of each item. |